A Brief History of American Tariffs

The Return of an American Tradition

When President Trump declared “Liberation Day” and imposed sweeping new tariffs on nearly all imports, markets convulsed and allies reeled. U.S. Treasury yields spiked, potentially ballooning interest payments on the U.S. debt, as the global economy seemed on the edge of a crisis.

But this wasn’t just a policy shock: it was the latest chapter in a centuries-old American tradition. As tariffs reemerge as a centerpiece of U.S. economic strategy, understanding their history is no longer academic; it’s essential. Tariffs affect everything from inflation and supply chains to diplomacy and national security.

Until the federal income tax was established in 1913, tariffs were the primary means used to fund the federal government, accounting for up to 95% of revenues in some years.

The history of U.S. tariff policy began with Alexander Hamilton’s landmark 1791 Report on Manufactures as Treasury Secretary. In it, Hamilton laid out a strategy for economic independence and industrial growth, proposing the use of tariffs to protect nascent American industries. His vision, later adapted into the American System, advocated using tariffs not only for revenue but to subsidize infrastructure development (“internal improvements” in the language of the time) and industrialization.

In 1790, Congress enacted a 5% tariff on most imports, enabling the young federal government to generate revenue while reducing direct taxation on citizens and states. Hamilton also advocated for export bans on key raw materials, tariff reductions on industrial inputs, patent protections, product standardization, and the development of transportation and financial infrastructure. These recommendations shaped U.S. economic policy for more than a century.

Tariffs rose significantly during times of war. On the eve of the War of 1812, average tariffs stood at 12.5%. To fund the conflict, Congress increased tariffs to 25%, then to 35% in 1816, and up to 40% by 1820. Throughout the 19th century, the United States maintained some of the highest tariff rates in the world, especially on manufactured goods. This was not just protectionism gone wild; it was a vital source of revenue, and the Constitution had limits on taxation that made income taxes difficult to impose.

Tariffs were deeply divisive leading into the Civil War. The industrial North favored high tariffs to protect factories, while the agrarian South, reliant on cotton exports and global markets, opposed them. Abraham Lincoln, a Whig turned Republican and proponent of protectionism, famously declared: “Give us a protective tariff, and we shall have the greatest nation on earth.” During the Civil War, tariffs averaged 44%, used to fund the war effort and to subsidize railroad expansion and infrastructure.

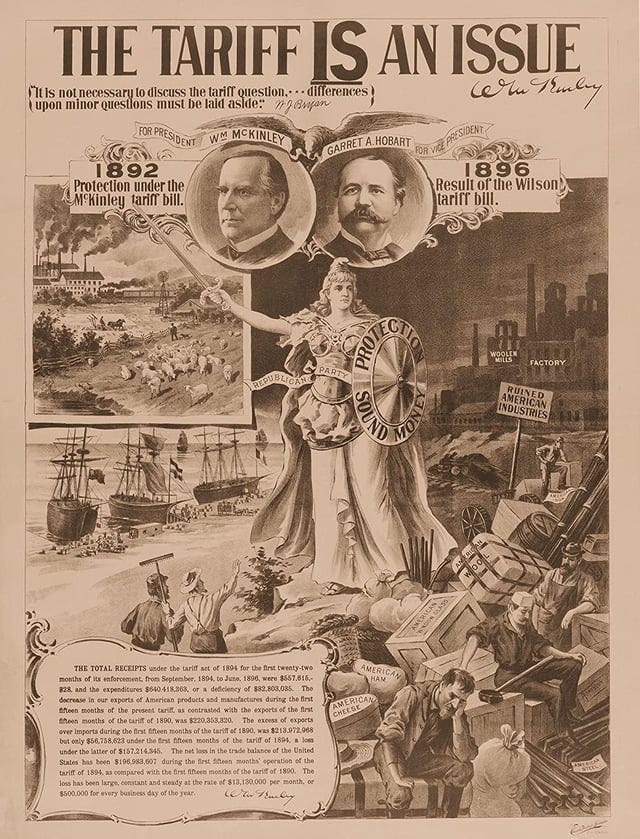

Following the war, the U.S. economy experienced rapid industrial growth, expanding at a 4.3% annual clip until 1913. By the late 19th century, as U.S. industries became globally competitive, tariff policy began to shift toward reciprocity. This meant matching tariffs with trade partners to encourage mutual reductions. The Democrats under Grover Cleveland criticized tariffs as favors to monopolies, while Republicans remained divided. The depression of 1896 helped pro-tariff Republicans under William McKinley regain power. McKinley advanced reciprocity agreements but maintained high tariff rates overall.

When Woodrow Wilson took office in 1913, a Democrat-controlled Congress passed the Underwood Tariff, reducing average rates to 26% and introducing the modern income tax to replace lost tariff revenue. This was done through the 16th Amendment, which enabled the federal government to impose taxes without regard to “apportionment among the several States, and without regard to any census or enumeration”. This marked a structural shift in federal finance that removed much of the rationale for tariffs.

The next major tariff shift came with the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930, which raised tariffs during the early stages of the Great Depression. Although later economic consensus holds that the Depression was caused more by monetary contraction and banking failures than tariffs, Smoot-Hawley became a symbol of protectionism gone awry. Global retaliation ensued, and world trade contracted sharply.

In response, Congress passed the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act of 1934, delegating tariff negotiation authority to the executive branch. This marked the beginning of a more cooperative, multilateral approach to trade policy. After World War II, the United States led efforts to liberalize trade globally through the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), culminating in seven rounds of tariff reductions. The final Uruguay Round led to the creation of the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 1995, establishing international mechanisms to enforce trade norms.

During this era, U.S. tariff policy was primarily retaliatory: tariffs were applied in response to unfair practices but otherwise reduced reciprocally. President Ronald Reagan followed this approach, promoting trade liberalization while targeting specific violations with focused tariffs. Reagan’s administration laid the groundwork for NAFTA and China’s eventual entry into the WTO. The 1990s and 2000s saw bipartisan support for free trade.

This consensus began to erode in the 2010s. Populist movements on both the left and right pointed to deindustrialization, offshoring, and stagnant wages as the consequences of globalization. In 2016, Donald Trump won the presidency with a platform that emphasized reshoring industry and confronting trade deficits, particularly with China.

In office, Trump reintroduced tariffs as a central economic weapon. In 2018, using Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act, he imposed tariffs of 25% on steel and 10% on aluminum, citing national security. More consequentially, Trump used Section 301 to levy tariffs on over $360 billion of Chinese imports, prompting Chinese retaliation. His administration also renegotiated NAFTA into the USMCA, added tariffs on European goods during transatlantic disputes, and threatened auto tariffs on allies.

Though President Biden retained most of Trump’s tariffs, he pivoted the rationale. Instead of focusing on bilateral deficits, the Biden administration framed tariffs as tools to protect critical supply chains, encourage domestic investment, and counter economic coercion from China. Trade policy was reoriented toward strategic decoupling rather than broad protectionism.

At the beginning of his second term, President Trump invoked the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA), citing persistent U.S. trade deficits as a national emergency and granting unilaterla executive authority to impose tariffs.. On April 3, 2025, Trump declared “Liberation Day” and announced a sweeping new tariff regime: a baseline 10% tariff on nearly all imports and much higher “reciprocal” tariffs on countries deemed to have unfair trade practices, raising the average effective rate to 22.5% — the highest since before World War II.

The announcement triggered sharp declines in equity markets and widespread concern among U.S. businesses and international partners over inflation, supply chain disruptions, and retaliation. Within days, China and the U.S. had imposed several rounds of retaliatory tariffs against each other, amounting to 145%. On April 9th, in an attempt to ease the backlash, the Trump administration announced a 90-day suspension of the elevated reciprocal tariffs for most countries — excluding China — while maintaining the universal 10% tariff.

Further adjustments are being made to address sector-specific concerns. On April 12, 2025, the administration announced exemptions for key technology imports from China, including smartphones, laptops, and semiconductor chips, that reduced tariff rates for these products to 20%. This carve-out aimed to limit consumer price increases and market losses, and protect critical U.S. tech supply chains.

These moves represent a decisive return to protectionism and a reversal of the postwar bipartisan free trade consensus. Tariffs are no longer narrowly tailored instruments of retaliation — they are now deployed as broad tools of industrial policy and national strategy. Looking ahead, this new regime could reconfigure global trade flows, provoke extended economic confrontation with key partners, and redefine America’s role in the global economy.

After nearly a century of liberalization, tariffs have reemerged as a defining instrument of American economic statecraft.