From Texas to Massachusetts

A Weeklong Drive Across the United States

I’ve been AWOL the last few weeks due to an extended roadtrip to the Northeast. It covered nearly 5,000 miles and lasted 10 weeks and in that time I stayed in Boston, New York City, and Washington. In acknowledgment of this, the next few history posts will be more of a travelogue than think pieces.

The trip started from my family’s home in the Hill Country of Texas on June 16th. Just a week later the peaceful Guadalupe River, only a few miles away, would become a raging torrent sweeping its way into national headlines. But I escaped that.

The trip across the country was long and reminds you how truly massive it is. My first stop was Boston, the farthest destination on my trip and just over 2000 miles from my starting point in Central Texas. My plan was to spend 7 weeks on the Harvard campus taking the final course for my master’s degree.

I drove up Interstate 35 through Austin, Waco, and finally to Dallas, where you then veer off onto Interstate 30 in the direction of Arkansas. I spent the night in Rockwall, just to the east of Dallas. Then there is the familiar drive to Little Rock through open prairies that transition to the piney woods of Texas and southwestern Arkansas.

Rather than take the usual route of Interstate 40 out of Little Rock, acrosss Tennessee, and to I-81 in Virginia, I drove up U.S. Highway 67 through northeast Arkansas into the flat, nearly treeless Mississippi River floodplain. Multiple states come together here, and in the space of an hour I crossed into Missouri, over the “Great River” into Tennessee and then north into Kentucky.

Woods and rolling hills stayed with me until I reached Lexington. East of here, the terrain quickly transitions to the rocky hills of the Cumberland Plateau and into the Appalachian Mountains. The rest of the trip was mostly in those mountains. The interstates going across the heart of West Virginia, from Huntington to Charleston to Morgantown, have some of the most incredible scenery of any highway in the United States.

The road winds between mountain ridges along stream beds and up and over mountain passes. Cruise control is impossible; the elevation changes constantly. This holds true into western Maryland. Its amazing to think how the early pioneers could have possibly managed this terrain.

I was determined to skip the major cities of the northeast until I reached Boston. From Hagerstown, MD, I took the interstate north to Harrisburg through the rolling hills just east of the mountains, dotted with farms. Then, I took the highway to Scranton back into the mountains and continued further east through more stunning scenery in the Hudson River valley and finally into Connecticut.

I was finally out of the mountains into the rocky hills that defined the last 200 miles to Boston. These don’t end until you reach the old inner suburbs such as Waltham, Arlington, and Newton. From here, you descend down to the rocky harbors, streams, and lakes of Cambridge and, finally, Boston itself.

It was easy to see why these far eastern regions where settled much more quickly and earlier than further west. Those mountains must have seemed impregnable to early settlers, and only later immigrants of the early 18th century went to the foothills out of necessity to obtain their own land. No one pushed much further until surveyors such as Daniel Boone, who discovered the Cumberland Gap that opened settlement in Kentucky, made this viable.

I stayed here in Cambridge for 7 weeks, at the oldest institute of higher learning in the United States: Harvard. It was founded in 1636 and endowed by a Puritan minister, John Harvard, whose statue is featured in the middle of Harvard Yard. Cambridge itself is one of the older communities in the US, founded by Puritans in 1636 just across the Charles River from Boston.

The dorms I stayed in were newer, in a regional take on the international style that might have been at home in the 1970s. But, they were off the historic Radcliffe College quad, consisting of student housing for the famous women’s college that was absorbed into Harvard in the 1990s. The quad also features older buildings from the first decade of the 20th century.

The housing was a half mile from the core Harvard campus, and to reach it meant walking across the Cambridge Common, also founded in 1636. A “common” in New England refers to the common pastures established in colonial settlements where farm animals could graze freely. As the towns grew, the commons shrunk to make way for development and eventually were reconstituted as community parks.

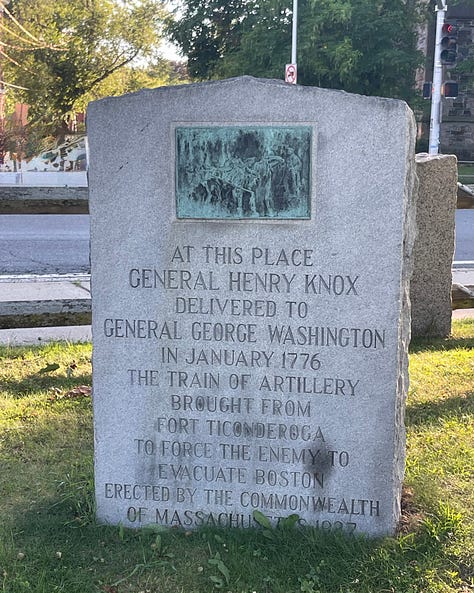

Cambridge Common, beyond its age, has its own significance. Here, the first militiamen of what became the Continental Army gathered just 10 miles from Lexington. George Washington traveled with his commission from the Continental Congress and took command of his army in 1775 on the common. His first headquarters was just a few blocks away.

Boston, of course, features multiple historic sites of the American revolution. Its Freedom Trail has, among other sites, the Queen Street Courthouse the site of the Boston Massacre and, appropriately, the place where the Declaration of Independence was first read publicly in Boston. There is also King’s Chapel, the burial place of colonial governors of Massachusetts, including one of my ancestors.

The home of Paul Revere is also here, who famously rode from Boston to Lexington to warn of British troops who were coming to seize guns and ammunition collected by colonial milita. There is an endless collection of other sites, and it could take months to cover all of it. There is the Bunker Hill monument in Charleston, the old rowhouses of Back Bay and Beacon Hill, the maze of red brick buildings in North End, the oldest residential neighborhood.

According to an old apocryphal quote, sometimes attributed to Mark Twain: “There are only four unique cities in the U.S.: New Orleans, San Antonio, Boston, and San Francisco". I’ve had the good fortune of living in Boston and San Antonio, and I can attest to the accuracy, if not the author.

Boston was America’s first urban center, and stands as a gateway from the Atlantic Ocean to the vast interior of the United States. This is how it was in the 17th century when Europeans first arrived here, and how it appears today. It is where many brilliant young people from all over the world first encounter the United States and its universities. And its where I ended up after a week-long journey halfway across a continent.