Greenland Is Better as an Ally Than an Asset

The renewed attention on Greenland has caught many people off guard. Until recently, it was the kind of place that appeared in defense planning documents rather than public political debate. But the fact that Greenland has reentered the conversation says less about novelty than about continuity. The United States has been thinking about Greenland for a long time.

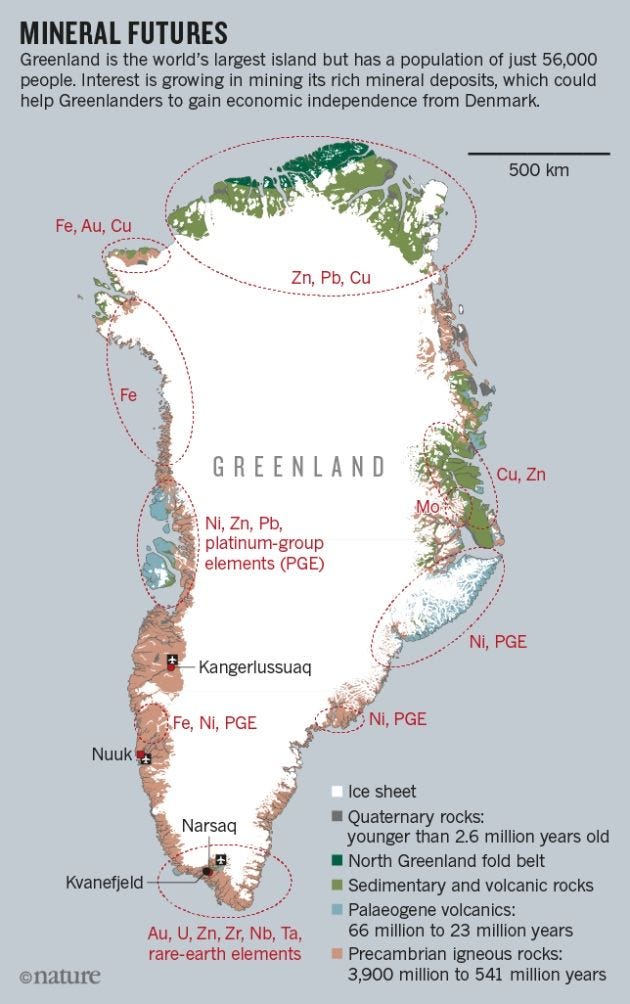

I’ve written about Greenland before and about why it matters to U.S. strategy. At the simplest level, the interests involved are not difficult to explain. Greenland has significant critical mineral deposits that matter directly for AI and semiconductor supply chains. Rare earth elements and related inputs are necessary for chip fabrication, advanced computing hardware, and the energy systems that support large-scale AI deployment. As Washington looks for ways to reduce dependence on China across these supply chains, Greenland naturally draws attention.

There is also a related economic interest tied to security. As Arctic ice recedes, shipping routes that once existed only on maps are becoming more viable. Greenland helps shape access between the Arctic Ocean and the North Atlantic. That matters commercially, but it also matters for military movement. Traffic tends to concentrate along routes that geography does not allow you to bypass.

The deeper reason Greenland has mattered to U.S. planners, however, predates both climate change and the current focus on chips. The shortest route from Washington to Moscow runs directly over Greenland. That is not a figure of speech. It is simply the result of great-circle geometry and the curvature of the Earth, even if some citizens with voting rights remain skeptical.

That geographic fact shaped U.S. defense planning during the Cold War. Greenland became a forward position for early-warning systems designed to detect Soviet missile launches. At its peak, the American military presence on the world’s largest island was substantial. What remains today is smaller, but still central: Pituffik Space Base, formerly Thule Air Base, now operated under the Space Force.

The name change sometimes invites jokes, but the mission has not changed. Missile warning and space-domain awareness are closely linked, and Greenland occupies a position that makes both possible. That role alone explains why Greenland remains strategically important.

This history matters because it clarifies a point that often gets lost in current debate. The United States already has military access to Greenland. That access exists not because Greenland belongs to the United States, but because Greenland is part of Denmark, and Denmark is a treaty ally.

Denmark is not a symbolic partner. It is a capable European military contributor and a country that fought alongside the United States in Afghanistan. For decades, the U.S.–Danish relationship has delivered what American security planners need in Greenland. Danish officials have repeatedly signaled that they would accept an expanded U.S. military presence if circumstances require it. There is no access problem to fix.

The same logic applies on the economic side. Securing mineral inputs for chips and AI hardware does not require sovereignty. It requires contracts, trade negotiations, and long-term investment. Any serious development of Greenland’s mineral resources would take a decade or more regardless of ownership. Acquisition does not accelerate chip supply chains or shorten permitting timelines. It simply changes who bears the cost.

Those costs are not trivial. Denmark currently subsidizes Greenland’s budget by roughly $700 million a year. Acquiring Greenland would shift that obligation to Washington, along with the costs of governance and basic services. Recent proposals to offset those costs through direct payments to Greenlandic citizens resemble a corporate takeover strategy more than a coherent national policy.

Once this is accounted for, the case for outright acquisition becomes thin. The security benefits are already in place. The economic access relevant to AI and chips is negotiable. Ownership adds cost without resolving a real constraint.

The downside, by contrast, appears immediately. Danish leaders have had to issue public statements clarifying that Greenland is not for sale. European officials have openly discussed whether additional forces should be positioned there to signal that territorial integrity within the alliance is not optional. That reaction alone should give pause.

This view has been reflected in the reaction of Republican senators. In a speech on the Senate floor, Mitch Mcconnell said “Unless and until the president can demonstrate otherwise, then the proposition at hand today is very straightforward: incinerating the hard-won trust of loyal allies in exchange for no meaningful change in U.S. access to the Arctic.”

A delegation of senators is traveling to Copenhagen this week, and the position of the legislative branch they will communicate will likely be very similar. One member of that delegation, Senator Thom Tillis (R-NC), said “The actual execution of anything that would involve a taking of a sovereign territory that is part of a sovereign nation, I think would be met with pretty substantial opposition in Congress.”

For Russia and China, this situation is advantageous. Few outcomes serve their interests better than tension between the United States and NATO. Creating friction within NATO over a territory where U.S. access is already secure is strategically counterproductive.

This reflects a broader truth about power and relationships. In diplomacy, as in business, long-term advantage comes from reliability. States that behave as unpredictable counterparties may extract concessions in the short run, but they weaken every other relationship that depends on trust.

I have argued elsewhere that if Denmark were ever to offer Greenland for sale voluntarily, that would be a different conversation. What matters here is not a hypothetical transaction but the precedent it would set. Pressuring a treaty ally to surrender territory would undermine the strategic logic of NATO and violate postwar norms against acquiring territory by force.

Even if legal and ethical questions are set aside, the policy calculation still fails. The United States would assume new obligations, strain its alliances, and gain little it does not already possess. Greenland does matter. The Arctic does matter. But when it comes to securing AI and semiconductor supply chains, ownership is not the mechanism that advances American interests. It is the one most likely to erode them.