History Across Generations

Considering Family and the State

It was the winter of 2021, and my family was clearing out my grandfather’s home. It was a nice ranch house, built on a hill overlooking the over 800 acres of his cattle ranch. Ken Briggs Sr., or “grandaddy”, had passed away in a terrible coda to the year of COVID. He did not die of COVID but of a stubborn refusal to continue a life dictated by a dialysis machine. You are not a man of the Briggs family without this stubborn streak that sometimes leans into the irrational or self-destructive.

Considering his family, and the circumstances that brought them to Texas, this personality trait makes more sense. We discovered this from a gently used binder casually resting on a built-in bookcase. Inset on the inside front cover were three pictures.

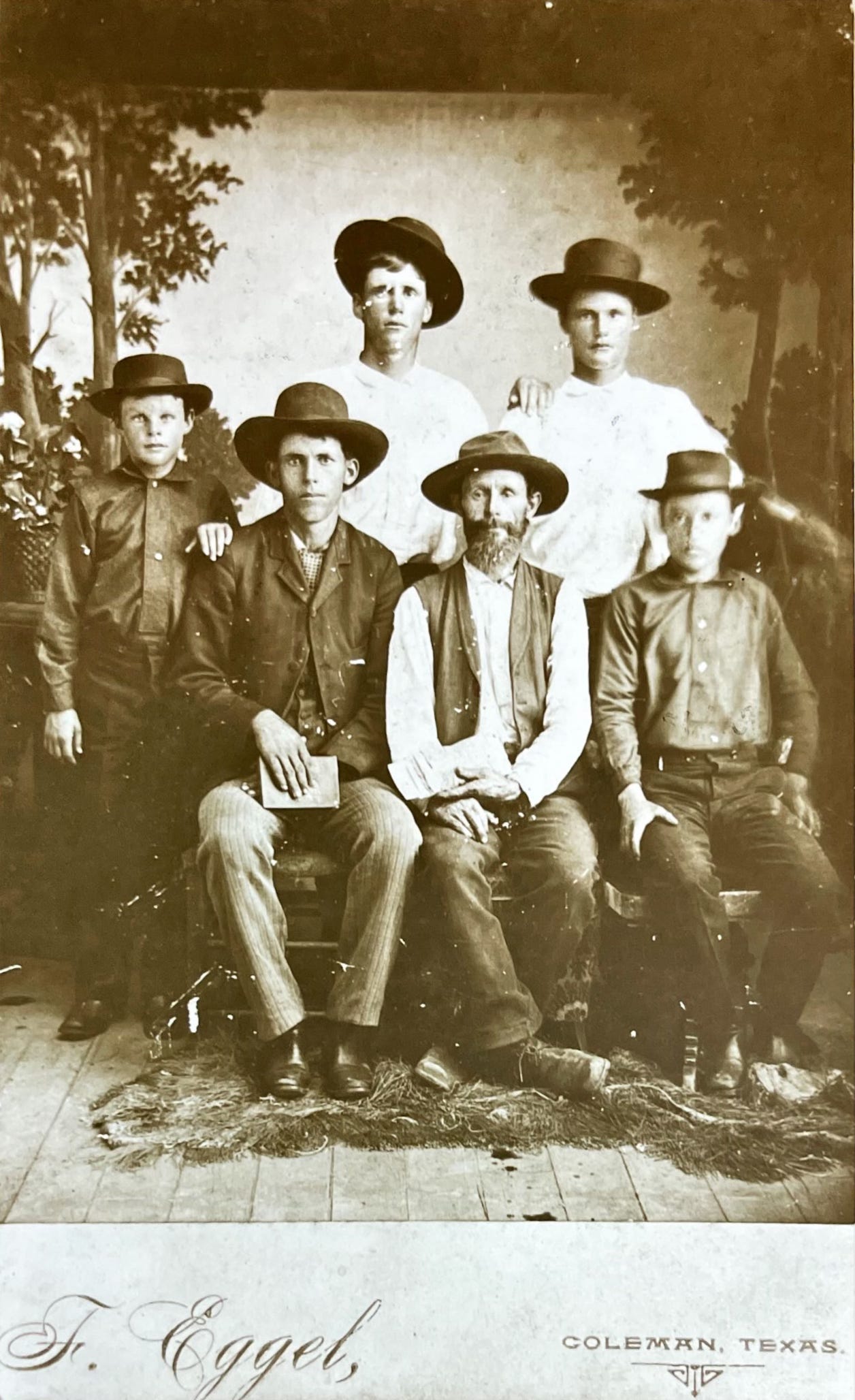

One of these was a picture of Elias Briggs, the first member of my clan with the Briggs surname to arrive in Texas, surrounded by his five sons. Elias’ birth year is given as 1839, so we estimated it was taken sometime in the 1890s. It was taken in the town of Coleman, TX, within an hour's drive of the geographical center of Texas.

Coleman is surrounded by rough country. It is 100 miles west of the Balcones fault line where the rolling, rich prairies of the gulf plain of central Texas give way to rugged hills, to the high plains, and finally to the American Southwest. It is characterized by endless dry prairie, dry grass, and a smattering of trees lining often-barren creekbeds.

At 16, Elias left home near Beardstown, Illinois, and made his way to Texas, never to return or have contact with his family. The Briggs were Scots-Irish settlers who arrived gradually starting in the Plymouth colony in 1631 to the Tidewater of Virginia in the mid-1700s.

This migration was driven by internal politics: the Stuart dynasty of England had united Scotland with England in a dynastic union, and they prioritized cleaning up the borderlands between the two kingdoms. Many of the Hatfield’s, McCoy’s, Nixon’s, Harrison’s, Briggs’ and others migrated to Ireland, and then to the New World.

The surname Briggs itself comes from the Middle English and Scottish word brig(g), which comes from the Old Norse word “bryggja”, meaning "bridge". The word was imported during the Viking invasions a millennium ago, suggesting lots of mixing between the Anglo-Saxons and Norsemen.

Being in the north of England, the region escaped the Latinization brought by the Norman invasions and remained distinct from the south of England. The Scottish-English borderlands became something of their own world, where people identified more with clans than kingdoms and fought each other.

That would change, and their descendants found themselves in a New World by way of geopolitical trends that made their way of life in the Old World untenable. The Briggs that landed at Tidewater possibly had an aversion to centralized government because of this, and over several generations, they lived on the frontier line, first in Appalachia, then to Indiana, and finally to Illinois.

By 1856, the frontier was even further west and ran in a line north from Central Texas. Elias moved, found himself in Dallas, enlisted in the U.S. Army, and was sent just beyond the frontier to a small post called Camp Colorado, near that small town of Coleman.

Other broader trends collided here. The Spanish had mostly avoided this territory beyond the Texas frontier, seeking to make peace with the powerful Comanche. It was essentially unexplored by white men before Texas joined the United States in 1845.

In the late 1850s, settlements began to encroach on the borderlands of Comancheria, and the U.S. Army directed the resources of the Department of Texas to create a series of forts and camps along the frontier line. In 1860, Elias was sent to one of those camps, Camp Colorado.

A quarter of the U.S. Army was in Texas then, and the last official command by Robert E. Lee before his resignation to join the Confederate Army was at Fort Mason. This made him the commanding officer of Camp Colorado. Here, the Scots-Irish relied on a centralized government for protection.

West Texas, even today, has a very friendly hospitable streak. East Texas is still friendly, but there are vestiges of the landed gentry and their more structured views on who deserves respect and who does not. The latter’s aversion to the federal government is based on the historical struggle between an established local culture against a larger power.

The reverse was true in West Texas. Here, the presence of local power was fundamentally reliant on, and thus not antagonistic to, federal power. The Confederate government conceded somewhat on this point, allowing men to defer their enlistment to man the border posts. Notably, several counties in the southern portion of the frontier voted against secession.

As the Comanche were driven back, and the perils of the old West receded, these settlers who lived under constant threat turned the rugged land into something livable. They raised cattle and created a temporary industry driving them to far-away railheads. Eventually, the rail lines reached even Coleman, and ranching became a more domestic affair.

Life continued. Elias and his sons moved further west to San Angelo, where my great-grandfather was born, and then back to Coleman. Unlike Elias himself, his children and their children stayed close. It was still hard.

WWI would take the young men while the Spanish flu devastated the old Texas frontier. My great-grandmother lost both parents and two siblings. My grandfather’s older brother died of tetanus from a cut by a piece of glass.

Then the depression came, and like the towns of the Midwest today, the towns of the Dust Bowl shriveled. Many, including Coleman, have not recovered to their 1930 population. Highways and the automobile drove more people to central cities as the importance of the railways diminished.

The vestiges of the short-lived frontier itself became part of an old world. They survived in the small towns, the abandoned buildings scattered throughout, the old wood fences, and the ranch foremen’s homes. There is even an abandoned military cemetery missing its Army post. Camp Colorado was abandoned in 1861 and never recovered.

This is some of the only evidence of the old world. There are also photographs and histories, and the legacy passed down across generations written in the chemical code that created us. The fates of nations and our history are written here.