How a Corporation Conquered India: Part I

English Traders Gain a Foothold

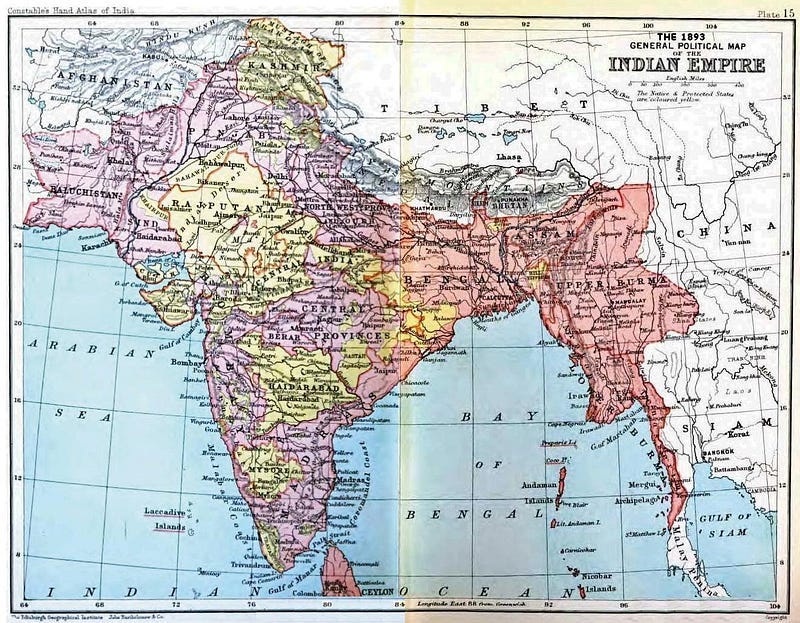

The Indian subcontinent has long been a diverse kaleidoscope of nations, languages, and cultures. Never a truly united nation, India has passed through alternating ages of union and disunion. The gradual expansion of colonial Britain into inland markets from isolated trading posts created the united India we know today.

The process of conquering India began 200 years before it was officially part of the British Empire. The English East India Company (EIC) was founded in 1600 by a group of adventurous merchants who petitioned Queen Elizabeth I for permission to sail to the East Indies and establish trading posts in the region. They followed in the footsteps of English naval officers such as Francis Drake, who traveled there to plunder the cargo of captured Spanish and Portuguese merchant vessels.

The Queen granted a charter for a 15-year monopoly on English trade between the Cape of Good Hope (South Africa) and the Straits of Magellan (Indonesia). She hoped to break the trade monopoly of the Portuguese Empire.

Sir James Lancaster commanded the first voyage, sailing to the Strait of Malacca. On the way, he seized a Portuguese vessel and used the stolen cargo to build factories on Java and the Spice Islands. These factories were trade zones where local merchants could interact with foreign merchants under the protection of a kingdom. The EIC operated and governed its factories under the authority of the Queen’s charter. They were essentially political dependencies of the Company.

This first English voyage broke the Portuguese and Spanish trade monopolies and struck a fatal blow to the Spanish Empire in the undeclared Anglo-Spanish war that had raged for 20 years. A second and third voyage closed out the decade and firmly established the English spice trade, despite competition from the Dutch.

The first landing on mainland India occurred on this third voyage in 1608. By 1611, the Company had established factories here and on the east coast at Machilipatnam. The success of these four trading posts led James I to renew the Company charter indefinitely.

Given the hostilities between the English and other countries conducting trade, such as the Dutch and Portuguese, these trading missions also assumed a military character. Trading vessels doubled as naval vessels. There was no clear separation between the Company and the military authority of the kingdom who chartered it.

The EIC established control of its trading posts with naval victories against the Dutch and Portuguese in 1612. With these coastal footholds secured, the EIC turned towards expanding its territorial foothold into mainland India and establishing relations with the Mughal Empire, which controlled most of India.

The royal charter vested the Company with all military and governmental authority required to facilitate its trading activities. It had full responsibility for its trading posts, including their security and governance. The Company functioned as a state within the areas it controlled, and its naval and security forces operated with the guarantee of the British crown.

However, this authority did not extend to diplomatic relations, and in 1612 James I dispatched an ambassador to visit the Mughal Emporer and arrange a commercial treaty giving the Company exclusive trading rights in Surat and other regions. Promises of goods from the European market persuaded the Emporer.

The EIC gradually expanded its commercial trading operations along the coast, eclipsing the holdings of the Portuguese Empire. By 1647, the EIC owned 23 factories in India. Beginning in 1634, the Company established trading posts in Bengal (modern Bangladesh), giving it a foothold on the eastern coasts of the subcontinent.

English dominance of Indian trade was finally secured by the transfer of Bombay to the EIC by the Portuguese in 1668. All areas where the EIC established its trading posts were subject to the same stipulations as the original 1612 arrangement. This means that in the process of establishing, securing, and maintaining coastal trading posts, it had effectively gained political control of those portions of the Indian coastline. Other European powers with a presence on the Indian coast, including Portugal and the Dutch, did the same.

These outposts became the beachheads from which the EIC gradually asserted political, economic, and military control of the Indian subcontinent.