M23 and the Fragile Idea of Borders

The Ongoing Ripples of Genocide

Much of history, and much of today’s headlines, still revolves around the “great powers” and the legacy of Western states. Even the well-intentioned label “Global South” lumps the histories of diverse, post-colonial nations into a category defined by exclusion from the “North.” Yet as the race for critical minerals accelerates, attention is turning to Africa, where resource wealth collides with fragile states.

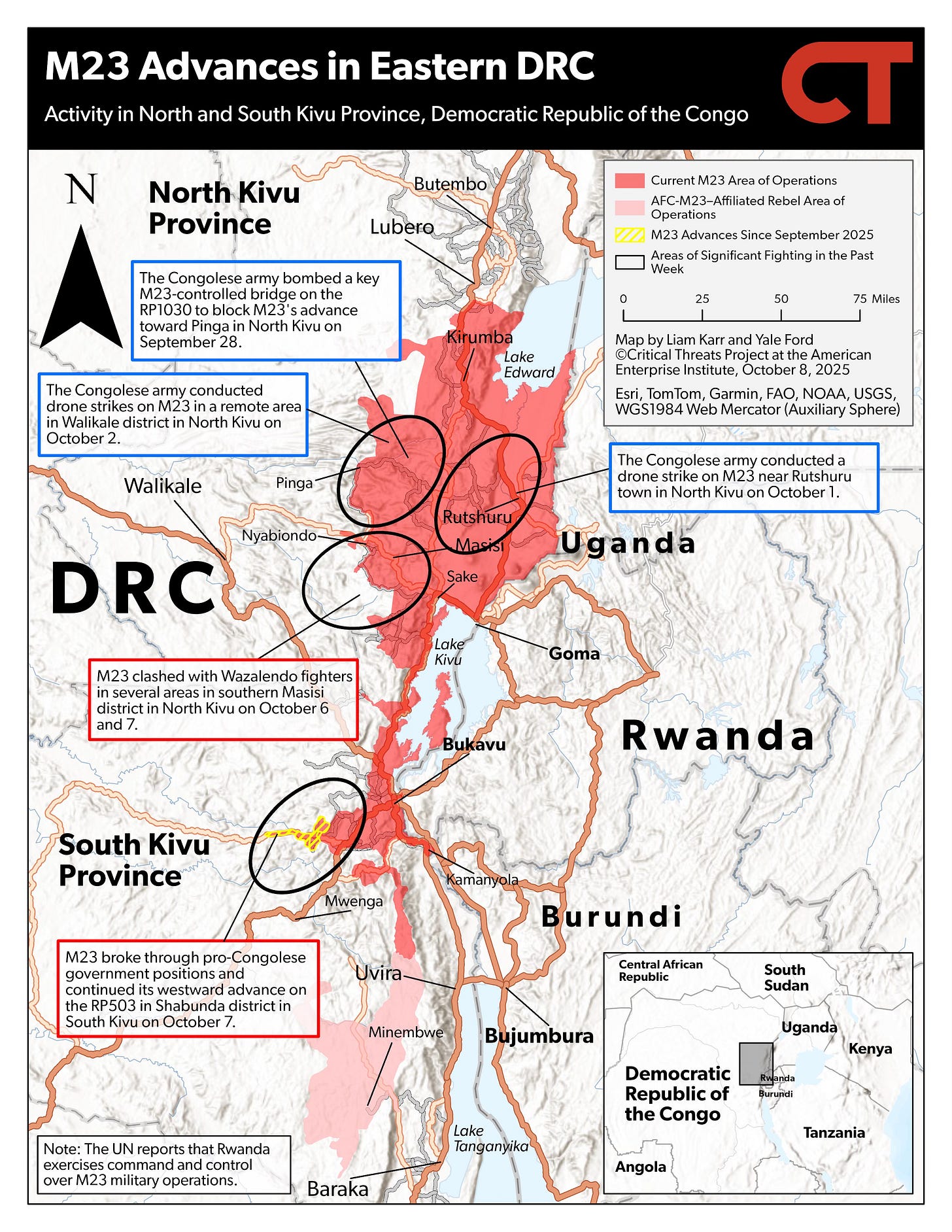

Nowhere is this clearer than in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). The M23 movement, a Tutsi-led insurgency with roots in Rwanda, has seized territory in the eastern part of the country, threatening Goma, a city of more than a million.

UN peacekeepers are preparing to depart after decades on the ground. Rwanda and Congo are trading threats. Hundreds of thousands have been displaced in just months. It is one of the deadliest conflicts in the world today, yet remains undercovered outside Africa.

M23’s rebellion is not a new story. It is the long echo of the 1994 Rwandan genocide, the distortions of colonialism, and the erosion of one of the twentieth century’s defining principles: the inviolability of borders.

The story begins in Rwanda. When the genocide against the Tutsi erupted in 1994, more than a million people fled into Zaire, as the DRC was then known. Among them were génocidaires and armed militias, forced out in the campaign by Tutsi rebel leader and current Rwandan president Paul Kagame that ended the genocide.

Some refugee camps were militarized and used as bases to launch raids back into Rwanda. Rwanda, newly under Tutsi-led rule, backed Congolese Tutsi militias that saw themselves as protecting kin across the frontier. This led to the First Congo War in 1996, which ended when Tutsi rebels backed by Uganda, Rwanda, and Angola overthrew the government of Zaire, renaming it the DRC.

In 1998, the Second Congo War erupted after the new DRC government expelled Rwandan forces and sought backing from other African nations. A new uprising of Tutsi groups near the Rwandan border led to “Africa’s World War” drawing in nine countries and leaving over 5 million dead. Even after a 2003 peace agreement, a Congolese-Tutsi faction known as the CNDP maintained a foothold in the North Kivu province on the Rwandan border

M23 itself traces back to a March 23, 2009 peace accord between the DRC and the CNDP. The deal promised integration with the armed forces and community protections. Instead, it unraveled. In 2012, former CNDP fighters mutinied, taking the name March 23 Movement.

They briefly occupied Goma before being pushed back by UN and Congolese troops. The group faded but never disappeared, as discrimination against Congolese Tutsis, weak state authority, and Rwanda’s pursuit of influence and minerals, remained unresolved.

By 2021, M23 returned with renewed force. Covertly backed by Rwanda, it has seized wide swathes of the eastern DRC, massacred civilian populations, and created over 1 million refugees. The rebellion is more than an ethnic dispute or a failed peace deal. It reflects the fragility of African borders drawn by colonial powers and the declining will to respect them.

Colonialism’s impact is unmistakable. Belgium governed Congo through division and extraction, while colonial authorities in Rwanda hardened fluid identities into rigid ethnic categories. These policies laid the groundwork for the 1994 genocide and for the violence that spilled across borders. Today, colonial-era lines still leave Tutsis trapped between states: never fully secure in Congo, never fully embraced in Rwanda.

In 1964, the Organization of African Unity declared colonial borders sacrosanct, reasoning that reopening them would ignite endless conflict between the newly independent nations of Africa. For decades, that principle held. In eastern Congo, it is breaking down. Rwanda asserts interests beyond its frontier, while the DRC claims sovereignty over territory it can’t control. M23 straddles the line between local insurgency and foreign proxy, eroding the very idea of sovereignty.

This breakdown matters globally. Inviolability of borders has been a cornerstone of international order since World War II. When it frays in Congo, it is part of the same story seen in Ukraine and elsewhere: states probing how far they can go in redrawing maps. Russia has tested this principle to its limit, using support of armed rebel factions to control politics in Moldova, Georgia, and, prior to its full-scale invasion, Ukraine.

It also has material stakes. Eastern Congo holds vast deposits of cobalt and other critical minerals essential to batteries and electronics. The very provinces destabilized by M23 are central to the semiconductor and battery industries. The conflict is not only a humanitarian disaster but a threat to supply chains the world depends on.

M23 is both symptom and accelerant: born of genocide, sustained by colonial legacies and ethnic tensions, and thriving in a space where ethnicity, resources, and neighboring ambitions outweigh sovereignty. Its rise underscores the danger of a world where borders, once fragile glue for peace, no longer hold.