Old Roots of the Blue Ridge

Continuing my travelogue, but not necessarily in chronological order, this post covers a portion of my return trip from Washington D.C. to Texas. My major goal for the return trip was to drive the Blue Ridge Parkway. It is the longest linear park in the United States at 469 miles and extends from western Virginia through North Carolina, and finally ends in the Great Smoky Mountains national park.

To get there, I drove southwest out of Washington, D.C. and across the northern Virginia to Charlottesville. I was greeted on the route by a sign pointing to Monticello, the estate of Thomas Jefferson. From Charlottesville, it was a quick drive west along 1-64 to the entrance of the Blue Ridge Parkway.

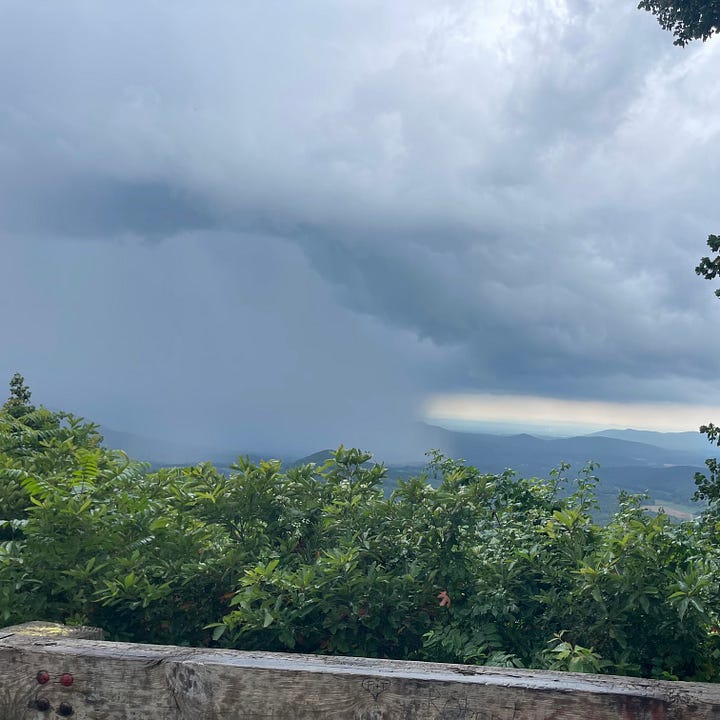

I entered the parkway in the early evening. It is a winding two-lane road that took me along mountain ridges and had periodic lookouts with some picture-perfect views. Heavy fog greeted me on some sections. As it got later, I decided after about 60 miles that I should stop to avoid driving through fog at night. That led to me accomplishing a bucket list item: camping in a national park.

I pulled over at one of the many rest areas and campgrounds. I found a secluded spot to park my Chevy Traverse for the night. The setup was simple. I use a power wheelchair with multiple functions that essentially allow me to fold it open as a makeshift bed, with full back recline and extending leg rests. It was really just a matter of putting up privacy screens on windows.

I did not anticipate the sheer blackness of night without artificial lighting. By 9 pm the sun had set and I had to retrieve blankets from the trunk. I deployed the side-entry ramp, and was enveloped in a darkness I had not experienced; I quickly returned inside, got an LED lantern, and proceeded.

Another unaticipated problem was bugs. I plugged my LED desk lamp into my solar-powered battery pack to do some writing inside my car. In a few minutes, the roof was host to lady bugs, moths, and flies. A lost cause without bugscreens, I turned off the lamp and decided to go to sleep. After waking up early, the journey continued pest-free.

The winding road continued. In the morning there was a heavy fog, but as the sun rose over the mountain ridge, it thinned and then cleared. The vistas were incredible, but became background noise with familiarity. I wound through slowly. By mid-afternoon I arrived in North Carolina.

This drive is part of my family’s heritage. My family’s lineage goes from Texas to Illinois, Indiana, and Kentucky and disappears into the mountains of Virginia. I can’t trace them directly from this point, but the context suggests my ancestors were part of a wave of Scots-Irish immigration in the 1720s and 30s that arrived in Chesepeake Bay.

A brief history lesson, the Scots-Irish, or Ulster Scots, were migrants from the border lands of England and Scotland who moved to Ulster, Ireland in response to various political events on Great Britain. The first wave was shortly after the dynastic union of England and Scotland in 1601, with the intentional ressetlement of the often warring border clans.

Subsequent waves continued until the early 18th century. These migrants, protestants on an island of Catholics, migrated further to the New World. They brought their folk music with them, which is where this American story gets very interesting.

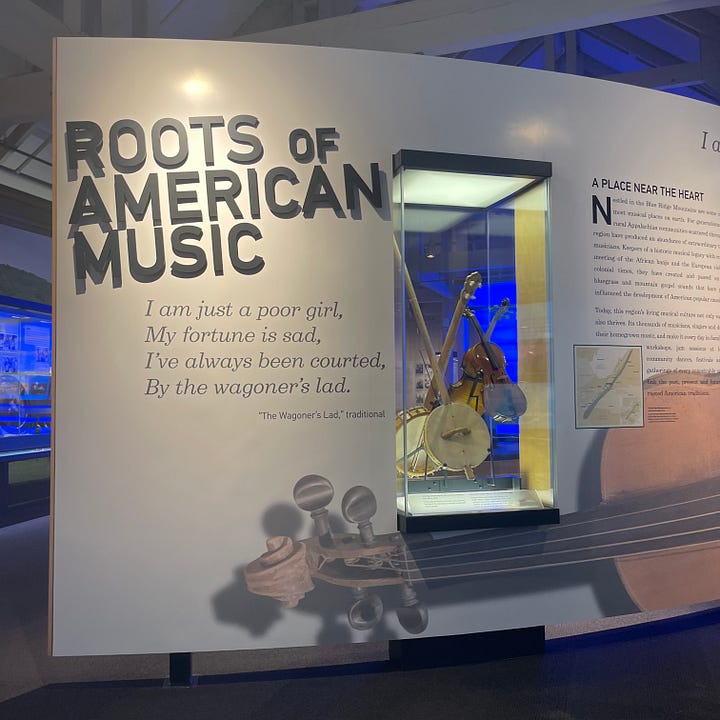

Shortly before crossing the North Carolina border, I came across a facility called the Blue Ridge music center. Inside was a small museum called The Roots of American Music. It showcased the unique fusion of Scots-Irish folk music and spirituals, from which modern folk and country-western music are ultimately derived, with the music of African Americans.

The patterns of blues, gospel, and soul music ultimately originated in West Africa. I also learned here that the precursor to the bango originated in the same place. A great cultural exchange occured in these mountains. The banjo itself became associated with country and folk music, moreso than African-American music traditions.

But this was the root of modern American music in a place that suggested my ancestors may have very well contributed to it. It also stands as a testament to the unique cultural heritage of America, which at its very heart lies the exchange of ideas and cultures from migrant groups that came together from very different parts of the world.

I would offer that this signifies the true heritage of America, rather than the nativist assertion that only those descended from white Europeans are true “heritage-americans” that is in vogue among national conservatives. Some of us just got here later.

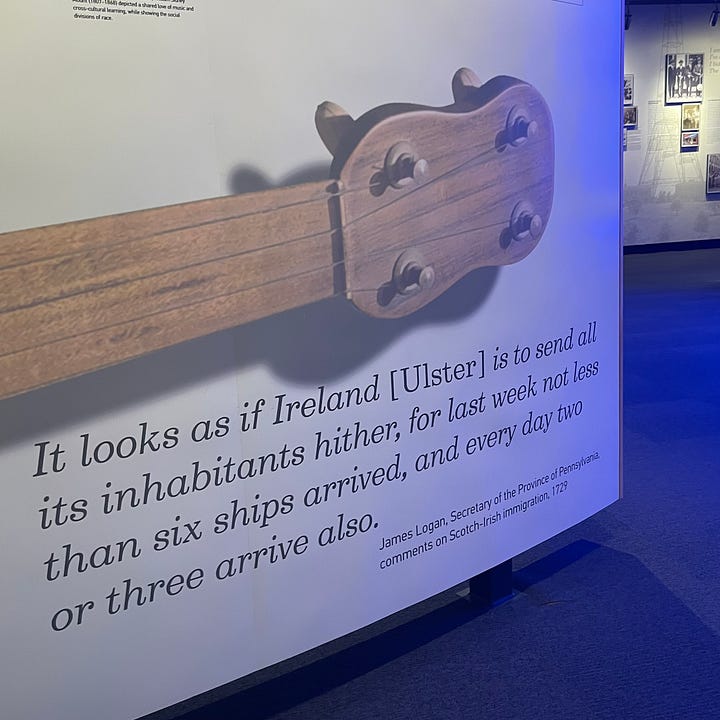

Another note: In this museum was a quote from a colonial official in Pennsylvania, who complained that “It looks as if Ireland [Ulster] is to send all its inhabitants hither. . . .” This sounds nonsensical today: Americans complaining about white protestant migrants from Britain 300 years ago.

The rhetoric of nearly 200 years ago complaining about Irish and Italian immigrants seems silly as well. And my bet is, 100 years from now, Americans will feel the same way about people from countries that are just now arriving here, to make their unique contribution to the American heritage.

But that’s enough pontificating on immigration. After leaving the museum and crossing into North Carolina, only the first thirty miles were open. Hurricane Helene had devestated this area nearly a year before, and most of the North Carolina section of the Blue Ridge Parkway was still closed. I followed alternate routes until I arrived in Asheville.

The next day was the drive along I-40 through the Great Smoky Mountains. The destructiveness of Helene was the most dramatic here. An interstate highway was reduced to a two-lane road for about 50 miles. Here, it mostly followed along the bed of the Pigeon River, a tributary of the Tennessee River. It had flooded in the aftermath of Helene, and the side of the highway closest to the river was closed.

A massive new embankment was under construction to prevent future flood damage. But eventually the road widened back in Tennessee and the land opened back up as I left the Smoky Mountains. From here, I drove through Knoxville and then out onto the Cumberland Plateau and out of the Appalachian mountains, this time for good.