Removing Maduro May Have Been a Strategic Mistake

Regime Change in Venezuela

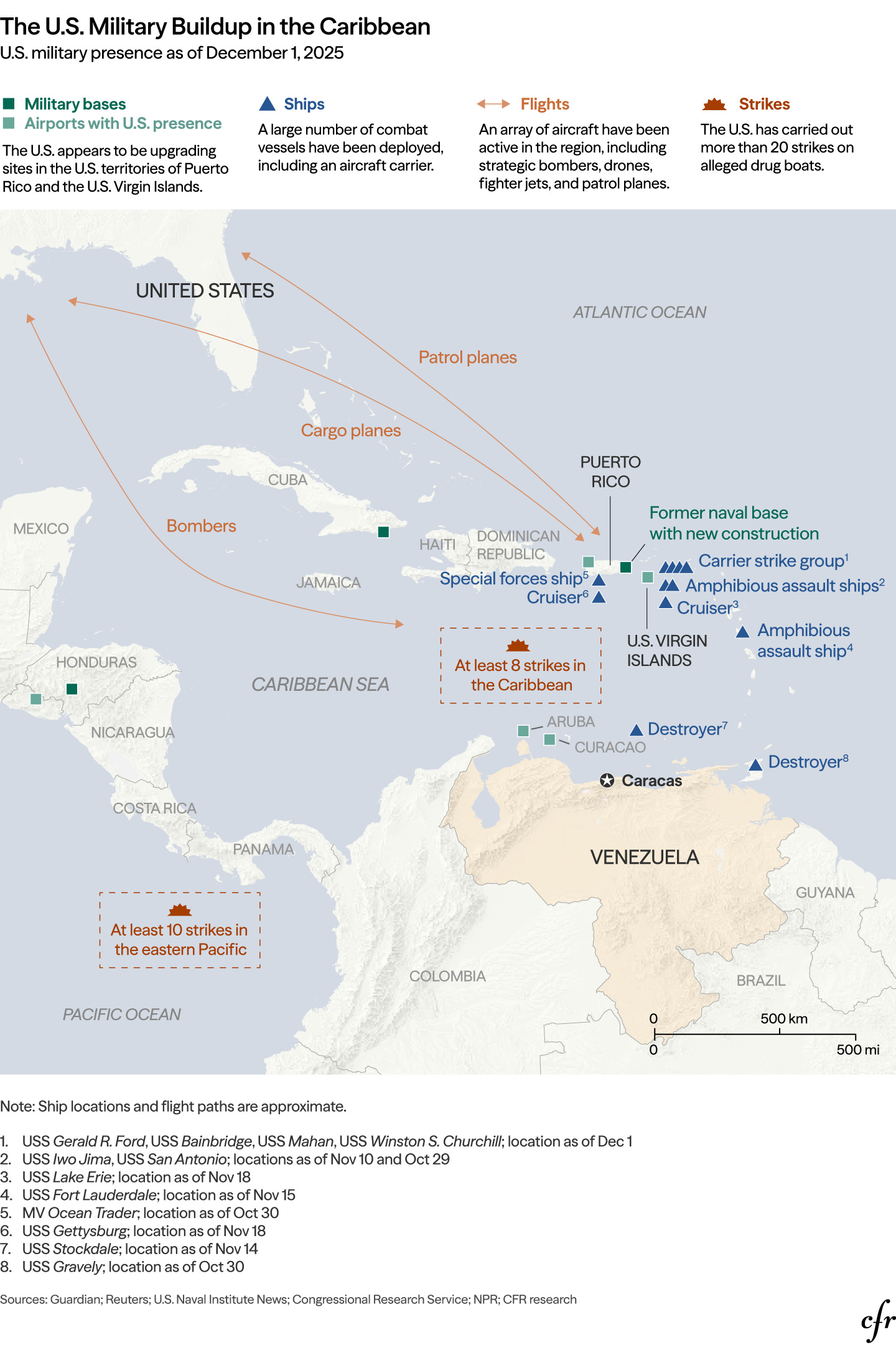

In a dramatic start to 2026 only three days in, the United States removed Nicolás Maduro from power and transferred him to U.S. custody to face federal charges. The Trump administration has defended this as a law-enforcement action rather than an act of war.

Regardless of how it is labeled, the decision amounted to the forcible removal of a sitting head of state. The more interesting question is not whether Maduro deserved it (he certainly did), but whether removing him actually advances U.S. interests once the downstream consequences are considered.

One of the most persistent failures in U.S. foreign policy is evaluating actions based on how decisive they look in the moment rather than how they reshape the system over time. Actions are taken to solve the problem immediately in front of policymakers, while second- and third-order consequences are treated as abstract or hypothetical. Those consequences are rarely hypothetical. They are simply delayed.

Venezuela never posed a serious threat to the United States. Its oil production is roughly 900,000 barrels per day, while the United States produces more than 14 million. Venezuela’s military has no ability to project power beyond its borders and is focused almost entirely on internal security.

Whatever one thinks of Maduro, his government was an irritant and a symbol, not a strategic danger. Treating his removal as urgent national security action required inflating the threat well beyond the underlying facts.

That threat inflation matters because it drives extreme solutions. Removing Maduro may feel like solving the problem, but it does not dismantle the system that produced him. Venezuela is not a personalist dictatorship that collapses when one individual is removed.

It is an entrenched one-party authoritarian state integrated with the military, intelligence services, and armed civilian groups that have grown wealthy and powerful under the regime. Those actors do not disappear with Maduro. They adapt, resist, or fight among themselves.

Turning an authoritarian state into a stable democracy through force has only succeeded under very specific conditions: total defeat, full occupation, and years of institutional reconstruction. Postwar Japan and West Germany met those conditions. Venezuela does not.

Iraq shows the opposite problem. Decades of intervention produced neither stability nor durable democratic governance. The irony is that ending regime change and nation-building was a core promise of the political movement now defending this action.

The administration framing Maduro’s removal as a law-enforcement operation rather than an act of war only deepens the strategic damage. No state can forcibly enforce its laws inside another sovereign country without consent.

Labeling does not change that reality. Acts of war are defined by what is done, not by how they are described. Treating this as a legal technicality undermines the credibility of U.S. commitments to international law rather than protecting them.

The selective nature of the justification also raises doubts about intent. Drug trafficking charges are elevated in some cases and ignored in others. Pardons are granted elsewhere while indictments are weaponized here. That creates the appearance of a legal pretext for a political decision that had already been made. Once that perception takes hold, the damage is not limited to Venezuela. It weakens confidence in the entire international legal framework the United States relies on to constrain other powers.

The regional consequences are already apparent. Public threats and coercive rhetoric directed beyond Venezuela, including toward Colombia, have unsettled Latin America. Colombia is one of Washington’s closest partners in the region, with its own internal security challenges and history of U.S. involvement. Signaling that leadership in neighboring countries could also be targeted sends a clear message: alignment with Washington is conditional and potentially reversible.

Faced with that uncertainty, regional governments respond rationally. They hedge. They diversify their economic and diplomatic relationships. China is already the largest trading partner for much of South America.

Regional blocs have expanded ties with Europe. These shifts are not endorsements of Maduro or authoritarianism. They are efforts to reduce exposure to an unpredictable United States. The net effect is declining U.S. influence.

There are also broader global implications. When the United States acts as if proximity grants it special rights over other states, it reinforces the logic of spheres of influence. That logic does not stop in the Caribbean.

It is closely watched in Moscow and Beijing. Each time sovereignty norms are bent for convenience, it becomes easier for other powers to justify similar actions under their own regional narratives. The United States cannot credibly oppose that trend while contributing to it.

None of this means Venezuela should have been ignored. Enforcing sanctions on Venezuelan oil exports is legitimate. Aggressively interdicting sanctioned oil shipments linked to Russia is sensible.

Oil is not just about revenue. It is essential to sustaining war. Pressure on Russian energy flows matters, and it appears to be working in Ukraine, especially in an environment of global overproduction that is keeping prices low.

But none of those objectives required removing Maduro. Strict sanctions enforcement could have constrained both Venezuela and Russia without destabilizing the region or undermining international law.

The Cuban Missile Crisis remains instructive. The United States blockaded Soviet shipments to Cuba without overthrowing Castro. The goal was containment, not regime change.

My skepticism is shaped in part by my engineering background. Engineers are trained to ask what happens after an intervention, not just whether the intervention is possible.

Systems fail when decision-makers focus on one variable and ignore how changes propagate elsewhere. Foreign policy works the same way. You judge decisions by how the system behaves afterward, not by how bold the move looked at the time.

Removing Maduro may feel decisive. Strategically, it is a high-risk move with limited upside and significant downstream costs. That is not a strategy. It is a gamble, and the consequences will unfold long after the headlines fade.