The Forever Debt Ceiling War

Spare Us the Drama, Please

Unfortunately, the debt ceiling is making the news again. It’s the recurring fiscal crisis that Washington loves to hate and drives excessive media attention to the political class. Just as they want it.

Ignoring the parade of officials diving in front of cameras, the absurdity of the situation is apparent. Before the rise of the Tea Party in the late aughts, raising the debt ceiling was a boring, routine political exercise. It has been raised 61 times (CRS, 2022) since 1978, but since 2011 it has been the centerpiece of political knife fights over the deficit.

Return of the Debt Ceiling Twilight Zone

Last week, the Treasury Department issued its so-called “drop dead” deadline of June 1st to reach a deal on the debt ceiling to prevent a default. Republicans see the issue as an opportunity to signal uncompromising opposition to the Democratic administration, and so, on the surface at least, the two sides are miles apart.

House Speaker Kevin McCarthy successfully pushed a $1.5 trillion debt (CNN, 2023) extension through the lower chamber last week that imposes drastic spending cuts, including on some signature programs of the Biden administration. Democrats insist it’s dead on arrival.

The window to negotiate a new deal appears to be closing. A meeting between President Biden and congressional leaders, including McCarthy, at the White House ended with a performative walkout by the House Speaker. Right now, the focus appears to be on political signaling to party bases rather than working constructively on a deal.

Despite what news outlets report with breathless concern, none of this concerns me too deeply. The U.S. will never default on its national debt for the same reasons we won’t let large banks fail, and even more so. Why do I say this?

First, what is meant by “default” anyway? Put simply, it is the failure to meet debt obligations, i.e., make payments, when they’re due. This has consequences for the borrower, who will have less access to credit in the future, and on less favorable terms. For the creditor, this means not getting paid and a reduction in the value of the debt they hold.

In a more generic sense, default means the failure to meet obligations already incurred, whether from debt, bills of sale, or invoices.

In the context of the United States government, default would, in the narrow sense, be a failure to make interest payments on U.S. Treasury bonds or to redeem bonds that have matured. In the broader sense, it would be the failure to pay for goods or services already provided or to make good on any financial obligation, such as for paying defense contractors, employee salaries AND interest on debt.

Why would the debt ceiling crisis lead to a default?

In the 2022 fiscal year, the U.S. Treasury Department paid $475 billion in interest on the national debt, mostly on 3-, 5-, and 10-year Treasury bonds. While this may seem like an eye-watering sum, in the context of U.S. government spending it’s just pocket change. Compared to the projected $6.2 trillion of spending, interest on the debt is roughly 8% of the federal budget (CBO, 2023).

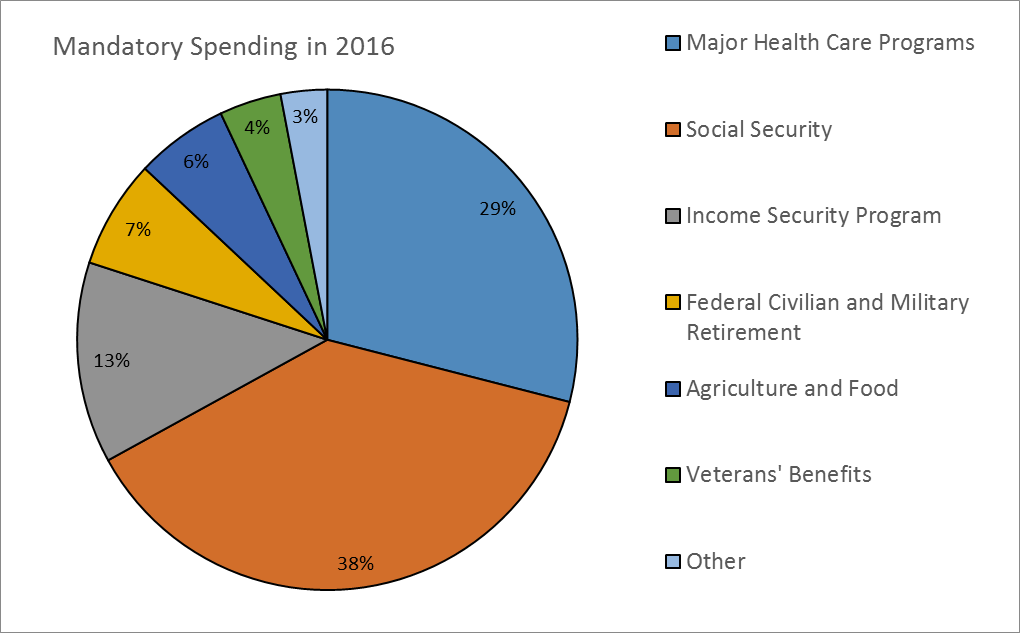

This number is climbing due to both increasing interest rates (now at roughly 2% on average) and continued borrowing (estimated at $1.4 trillion for FY2023). More significant is the ballooning cost of what is called “mandatory spending.” This is spending that is mandated by laws passed previously and is binding regardless of what Congress wants to do fiscally from year to year.

Outlays for Social security and Medicare are mandatory spending. Other forms of mandatory spending include various transfer payment programs, subsidies, and tax credits. It also includes benefits for veterans. The total of this spending was $4.1 trillion in FY2022 out of $6.3 trillion, or 65% of spending (CBO, 2023). Combine this with interest on the debt and you get around $4.57 trillion, which is over 93% of revenues for FY2022.

This leaves only 7% of revenues to cover the remaining 27% of federal spending, which is called “discretionary spending”, and means that Congress has the discretion to change this spending from year to year without changing existing law. This includes the $751 billion defense budget (CBO, 2023) that cannot easily be reduced without major changes in American defense strategy. The revenue left over after mandatory spending would only cover 44% of the defense budget.

Revenues don’t cover all the discretionary budget, meaning that the government must borrow to make up the difference. Last year, $1.4 trillion was borrowed. If the debt limit is breached, the United States could no longer legally borrow this money.

Overnight, the United States would lose 22% of its funds, meaning a 22% cut in spending would be required. Then prioritization would need to start, and this process could paralyze Washington. Obviously, the defense budget could not be zeroed out.

But, to prevent a cut of at least half the defense budget, Congress would have to revisit laws creating mandatory spending. In the meantime, an immediate 22% cut in spending would be required, and it would all come out of the discretionary spending budget.

Many of these expenses have already been incurred, as the borrowed money would go towards outstanding invoices first. These would have to be pushed aside, at least temporarily. Essentially, the government would be in default.

What would a default look like?

The unlikely debt default

First, let’s look at the most severe scenario (and the least likely). Failure to make good on Treasury bonds would precipitate a global financial crisis. 60% of global currency reserves are in dollars, and nearly 90% of foreign currency exchanges are facilitated in dollars. It is the most circulated currency in the world.

The mechanisms of what would cause this are complex and confusing even to me, but I’ll try my best to explain. At a basic level, not making good on U.S. Treasury bonds means they are less valuable. This would reduce the value of the balance sheet of the Federal Reserve, which holds a significant amount of U.S. Treasuries. These bond holdings are used to back money loaned out to the member banks of the Fed and count effectively as currency for this purpose.

Maintaining the required reserves would force a devaluation of the dollar and reduce its value on foreign exchange markets. It would also mean less money and credit in circulation, which is economically disruptive. It could also lead to a run on dollars as foreign holders of dollars rush to convert their cash to other currencies.

Again, the dollar is the number one global reserve currency. Its devaluation, as well as the devaluation of its derived financial instruments and reduced circulation, could trigger a global recession.

And that’s precisely why this scenario won’t happen.

Interest on the debt is only 8% of the budget. It can easily be covered by existing revenues. It is the spending that is the most mandatory, as Congress cannot simply pass a law waiving payments on treasuries. It could pass a law saying the payments would not be made, but this is hypothetical. Such a law would cause the value of Treasury bills to go to zero overnight.

In this scenario, the Treasury Department and the Fed would likely do what they must to make the payments and defy Congress. Their basis would be a section of the Fourteenth Amendment to the US Constitution which says:

The validity of the public debt of the United States, authorized by law, including debts incurred for payment of pensions and bounties for services in suppressing insurrection or rebellion, shall not be questioned. — Amendment XIV, Section IV

The consequences of not making these interest payments are so dire that the administration would employ every tool available to make sure it does not happen. Not to mention that bondholders would immediately take to court to seek relief for the destroyed value of their investments.

So, I’m not concerned about this scenario. In the same sense that, while hypothetically possible, I don’t expect income taxes to be abolished any time soon.

The federal government just used dubious authority to ensure all bank deposits, even for accounts over the $250,000 FDIC limit, to contain the damage from the failure of Silicon Valley Bank. Imagine what else it would do to stave off the global financial crisis caused by a failure to make U.S. Treasury bond interest payments.

The spending default

This is not to say that the discretionary spending cuts that would immediately ensue from breaching the debt limit would be no problem. On the contrary, they would cause a major disruption to ongoing military and diplomatic operations.

For example, a planned trip by President Biden to the G-7 summit in Japan and a meeting with the so-called Quad (US, Japan, Australia, and India) leaders in Australia would need to be canceled. The timing could not be worse, as the trip was to coincide with an executive order reducing outbound U.S. investment to China in economic sectors critical to national security.

The Pentagon would also be hurt by the sudden cuts. Previous cuts and threatened cuts as part of sequestration 10 years ago hurt military readiness (DOD, 2016). At a time when Russia is actively undermining the world order through its illegal invasion of Ukraine, and China is (literally) testing the military waters in the South China Sea, unplanned and sudden cuts in U.S. defense spending could be devastating to American defense strategy.

Former Defense Secretaries Leon Panetta and Chuck Hagel weighed in on this in a recent op-ed (The Hill, 2023):

To default on our financial obligations at this time would both undermine our own power and encourage Putin to continue his futile war on democracy.

In addition to the strategic consequences of cutting the defense budget in half, there are also consequences to all other discretionary spending cuts. Contractors would have payments on invoices delayed, which causes cash flow problems for these businesses and makes it harder for them to pay employees.

Additionally, departments and agencies would need to be closed and government employees furloughed until a debt ceiling deal can be reached. The work of the government, beyond making mandatory payments, would grind to a halt. This would cause major disruptions in government services.

Short of a debt ceiling deal, Congress would need to negotiate on which mandatory spending programs to cut, and which discretionary spending outlays to prioritize with those funds. Of course, if we get to the point where Congress cannot get a debt ceiling deal, it is unlikely that successful horse trading on spending priorities would be possible.

Conclusion: Let’s All Take a Chill Pill

So, I made that last bit about spending cuts sound bad. But I’m still not worried, and it’s for similar reasons that I’m not worried about a default on debt interest payments. Too many stakeholders will be hurt by a protracted debt ceiling crisis, and they will pressure Congress to cave, particularly the holdouts.

Republicans have donors, many of them with business interests that would be directly impacted. They also have constituents who live and work in communities with military bases, and they would complain about their unemployed family members and local officials would complain to their Congressman.

Just as happened ten years ago when a deficit reduction bill was agreed to, Congress would quickly come to a deal to mitigate the worst impacts of the crisis. And if the Republicans insist on a long-term debt reduction plan, let them have it. It can always be renegotiated later.

So, I’m not worried about a financial crisis, and I’m not worried about a protracted debt ceiling crisis, or the (very) temporary inability of America to pay its bills. Since the rise of the tea party movement 15 years ago, we’ve gone through this debt ceiling song and dance several times with the same tired talking points and come out fine on the other side.

Most of the antics surrounding this are political theater, including today’s walkout from the White House by Kevin McCarthy without a deal. President Biden knows McCarthy must make a show of resistance for his caucus and will come back to the table once a crisis is imminent.

The best outcome would be the elimination of the debt ceiling (which, due to the 14th Amendment, has dubious legality) in exchange for a long-term deficit reduction deal. Such an agreement would acknowledge the problem with holding our borrowing ability hostage, as well as a ballooning national debt and the resulting interest payment burden.

If we continue down our current path, mandatory spending will exceed revenues, and we will be in a trap of having to borrow to pay for the cost of previous borrowing. That would set us on a long-term path for fiscal and monetary disaster, and a dramatic reduction of American power and influence.

That is something worth being concerned about.

References

Congressional Research Service (CRS). (2022). R41814: The debt limit: History and recent increases.

https://sgp.fas.org/

CNN. (2023, May 2). McCarthy, Biden hold debt ceiling meeting. https://www.cnn.com/2023/05/02/politics/mccarthy-biden-debt-ceiling-meeting/

Congressional Budget Office. (2023). Budget topics. https://www.cbo.gov/topics/budget

Department of Defense. (2016). Sequestration poses biggest threat to readiness, military leaders say. https://www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/694480/sequestration-poses-biggest-threat-to-readiness-military-leaders-say/

The Hill. (2023). Debt ceiling brinksmanship weakens U.S. national security. https://thehill.com/opinion/national-security/3872431-debt-ceiling-brinksmanship-weakens-us-national-security/