The Hidden Strength in Democracy's Chaos

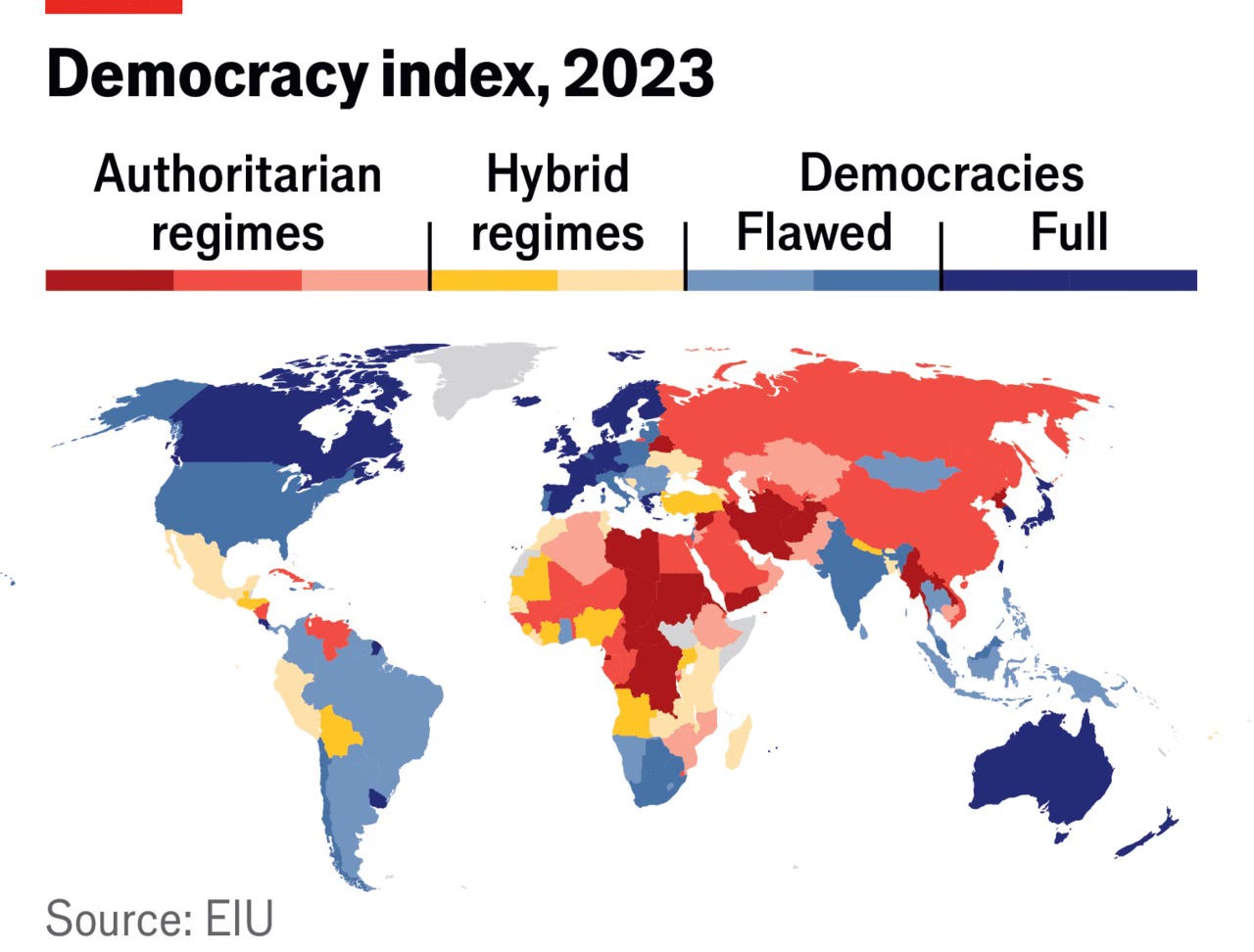

A theme I’ve picked up on in foreign policy discourse is a recurring one. China’s authoritarian, state capitalist system is allegedly superior to Western liberal democracy, which is also allegedly in decline. There is also concern about what is known as “democratic backsliding”, or the idea that existing democracies are going down an authoritarian path.

Examples that are often cited include the former communist states of Eastern Europe, such as Poland, Hungary, and Slovakia with nationalist, populist leaders. And the United States has experienced significant consolidation of power in the executive branch and divisiveness that paralyzes the regular political process.

Some even say we should welcome new systems like China’s, or at least look jealously at “efficient” systems where the leader makes the call, and that is that.

I was reading a Project Syndicate piece that asked who will model democracy now? The argument is straightforward: the U.S. and Europe have lost credibility, and the future of democracy will depend on how it fares in other countries, such as South Africa, Brazil, and South Korea, rather than copying Western blueprints.

There’s no doubt this diagnosis resonates. Political dysfunction in Washington is obvious. Europe is struggling with populism and gridlock. From the outside, Western democracy can look like a machine with too many broken parts. But here’s where I diverge: the messiness of democracy is precisely what makes it durable. The U.S. and Europe are still the models — not because they are perfect, but because they have proven able to survive crises, adapt, and recover in ways authoritarian systems cannot.

Take the U.S. economy after COVID-19. While commentators were predicting stagnation, the United States staged one of the strongest recoveries in the developed world. Unemployment dropped rapidly, growth rebounded, and while inflation surged, it was ultimately contained to a healthy 2% by the end of the Biden administration.

Other democracies in Europe also adapted quickly and rolled out vaccines at scale once available. These weren’t flawless responses, but they showed what democratic states do well: course correction in real time, with feedback from publics, markets, and institutions.

Contrast that with authoritarian systems. China’s “zero COVID” policy was touted as efficient, until it wasn’t. Lockdowns dragged on for years, dissent was stifled, and when the policy finally collapsed, Beijing had no clear exit plan. China’s GDP growth pulled back to a tepid 2%.

That flexibility is the heart of democratic resilience. The January 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol was a shock to America’s image, as was the series of legal maneuvers attempting to overturn the 2020 election results. Yet the transfer of power still occurred. Investigations followed. Institutions largely held.

Europe’s response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is another case: internal divisions didn’t prevent the EU from delivering unprecedented sanctions, coordinating defense policy, and sustaining military aid. Democracies often look divided at the start of a crisis but eventually adjust course as the political process plays out.

Authoritarian regimes, on the other hand, have a brittleness. In engineering school, we are taught how control systems with feedback loops are better at self-correcting and are therefore more stable. A democratic system has a feedback loop, but most authoritarian systems do not. Authoritarian leaders can decisively launch wars and make policy, but they are often blind to the merits of those actions, surrounded by people incentivized to tell the leader what he wants to hear.

This matters for foreign policy. If you are a policymaker in the developing world, you’re not just choosing between “democracy” and “autocracy” in the abstract. You’re asking: which system can deliver stability, prosperity, and adaptability in the face of shocks? China’s system offers order and decisiveness, but also opacity and brittle institutions.

Democracies, by contrast, can be loud, messy, and polarized, but the evidence of resilience is there. The United States itself, which is the world’s oldest democracy, has been the most powerful state in the world for a century. It outlasted the European empires, fascism, and Soviet communism.

So-called “middle powers” see this clearly. Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney recently argued that countries like his must thrive by building resilience at home and diversifying alliances. That’s democratic thinking in practice: legitimacy rooted in results, not just ideals. India, South Korea, and others hedge between Washington and Beijing, but they still model their governments on democracy.

The West can no longer simply point to itself as the universal blueprint. But that doesn’t mean it has lost its model power. Democracies can make mistakes, learn from them, and move forward. Authoritarian states often look efficient until they suddenly aren’t. Democracies look dysfunctional until, against the odds, they prevail.

So, who models democracy now? Still the U.S. and Europe, but not because others should clone their systems, but because they continue to show that resilience, openness, and self-correction are the most reliable paths to stability.