The Internet Runs on Cables, and Geopolitics is Putting Them at Risk

In March 2024, multiple subsea cable systems in the Red Sea were damaged within weeks of one another. The affected cables carried traffic linking Europe to the Middle East, India, and East Asia. Data was rerouted, speeds dropped in parts of Africa and South Asia, and repairs were delayed by security conditions. Nearly all global internet traffic moves through fiber-optic cables laid across the ocean floor, and those cables pass through places where physical security is tenuous.

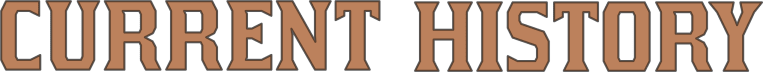

For most users, the internet feels abstract and placeless. In reality, it runs through a highly concentrated physical network of fiber-optic cables laid across the seabed, surfacing at fixed coastal landing points and passing through narrow maritime corridors. Roughly 500 subsea cables carry nearly all intercontinental data traffic, relying on a small number of heavily used routes and a limited global fleet of specialized repair vessels. When conditions deteriorate along these corridors, the effects ripple globally.

Satellites play a key role for remote access and redundancy, but they cannot match the capacity or low latency of fiber optics for network traffic. This physical infrastructure is also why states that control entry points can shape information flows. China’s Great Firewall is often described as a software system, but it rests on control over a small number of international gateways where subsea cables connect to domestic networks. The ability to filter, throttle, or monitor traffic begins with physical access.

Redundancy exists, but it is constrained. Laying a new cable can take five years or more from planning to completion. Coastal permitting is slow and political. Seabed geography limits routing options. Repair capacity is finite. When the Marea cable between the United States and Europe was damaged in 2022, traffic was rerouted within hours, but full restoration took weeks. The system bends before it breaks, but that flexibility has limits.

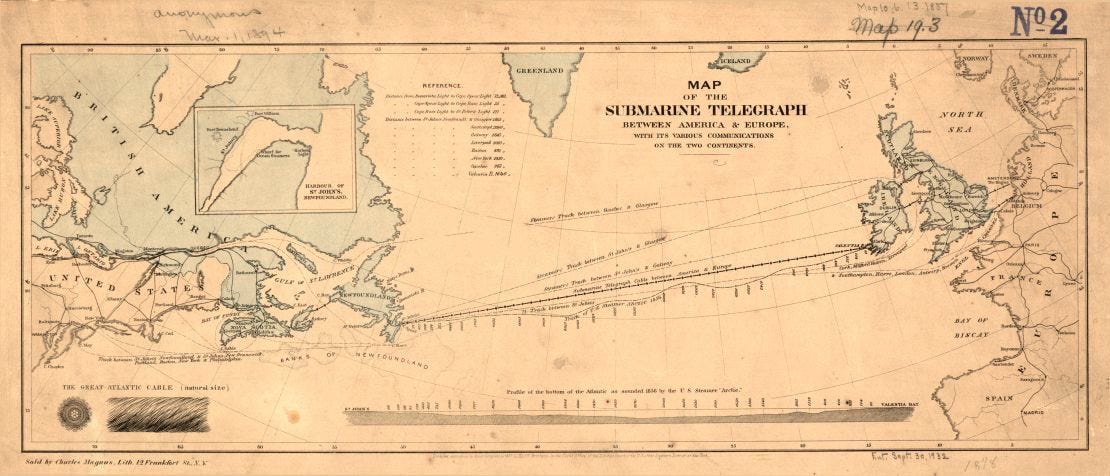

Geography concentrates risk in ways that are difficult to escape. Many modern cable routes follow paths first established by nineteenth-century telegraph lines. The North Atlantic remains the primary artery between North America and Europe. The Red Sea links Europe to Asia through the Suez region. The Luzon Strait connects East Asia to the Pacific. In the Red Sea, those pressures are no longer theoretical. Houthi attacks on commercial shipping since late 2023 have raised insurance premiums, fable projects have been delayed or rerouted, and repair ships have faced restricted access windows. The mere presence of instability causes problems.

Accidents and sabotage are also difficult to distinguish. In the Baltic Sea in 2023, damage to pipelines and cables triggered investigations that highlighted how vulnerable seabed infrastructure is in shallow, heavily trafficked waters. This drove the rapid response earlier this year when Russian-linked vessels were loitering over Baltic Sea cables. It is another potential avenue for hybrid warfare. But even when damage is unintentional, the effect on connectivity is the same.

For decades, subsea cables were treated as private commercial infrastructure. Companies optimized routes for cost and performance while governments focused on permitting and regulation. That division is breaking down. The United States has increased scrutiny of cable landing licenses for systems involving Chinese firms. Australia is funding alternative cable routes for Pacific island nations to reduce dependence on Chinese-backed projects. The European Union is mapping critical subsea infrastructure as part of its broader security planning.

Yet responsibility remains blurred. Ownership is often shared among consortia of telecom firms, cloud providers, and investors. Protection involves navies and coast guards that were never designed to guard thousands of miles of cable. When disruptions occur, it is not always clear who bears the cost or who should act first. Continuous protection of undersea cables is not feasible. Military presence provides little deterrence against actions that can be denied or disguised as accidents. As a result, resilience strategies focus elsewhere. Firms diversify routes where possible. Governments encourage redundancy in critical regions. Repair capacity is treated as a strategic asset rather than a routine service.

These choices reshape global connectivity over time. New capacity flows toward regions perceived as stable and politically aligned. Other areas see projects postponed or canceled. Africa, for example, has benefited from new east-west cables that bypass traditional chokepoints, while parts of the Middle East face uncertainty as Red Sea attacks persist. Power accrues quietly to states that control resilient pathways and can absorb disruption.

There won’t be a moment when the internet goes dark, so none of this appears as a single crisis. Instead, risk accumulates gradually. As maritime risk rises, subsea cables are among the first systems to feel the heat. The internet is not detached from the physical world. It is built on infrastructure shaped by geography, security, and politics. They reveal how global connectivity is stressed long before users notice, and how competition increasingly plays out below the surface rather than on the screen.