The Middle East’s New Map From the Gulf to the Caspian

The political geography of the Middle East is shifting in a way that would have been hard to imagine even five years ago. Kazakhstan, a majority-Muslim Central Asian state that most Americans do not associate with the region at all, announced plans this week to join the Abraham Accords. In Washington, Mohammed bin Salman arrives Tuesday to finalize a far-reaching security pact with the United States. Israel is now pushing for an unprecedented twenty-year aid package.

These developments are part of a much larger pattern. A growing commercial-security network now links states from Morocco to the Caspian, and it is pulling new players into what used to be a closed regional system. The United States is not returning to the old Middle East so much as presiding over the formation of a broader one. The different approaches of Biden and Trump help explain why this new map is taking shape.

Biden’s Approach: Stability and Familiar Boundaries

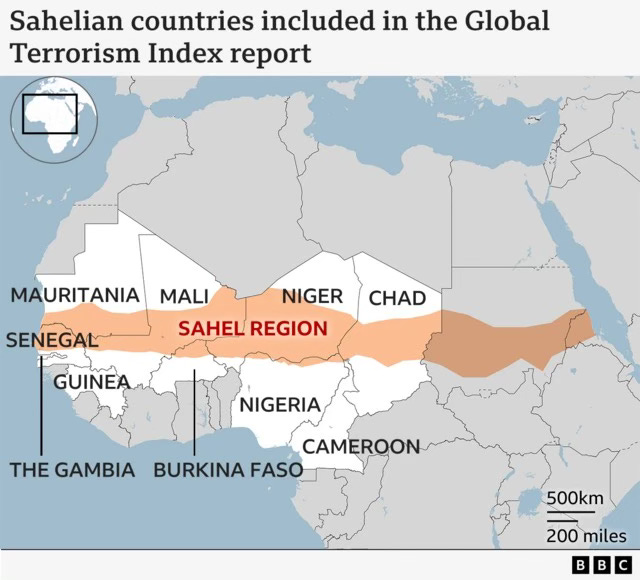

Biden’s foreign policy followed a familiar set of assumptions about how regions are organized. The Middle East, Central Asia, and the Sahel, as the transition zone from the Sahara desert is known, were treated as separate policy arenas, each with its own institutions and crisis-management tools. That structure guided which problems received attention and which ones were accepted as unavoidable features of the landscape.

Central Asia remained on the margins. Its main strategic value was as a logistical corridor for the war in Afghanistan. When that war ended, the region slipped back toward the periphery. The administration focused on Europe after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and placed its diplomatic energy into holding NATO and traditional democratic partners together. Washington encouraged diversification of Central Asian countries away from Russia and China, yet it stopped short of challenging their dominance in the region.

A similar pattern shaped the approach to the Sahel. Sudan’s collapse into civil war and west Africa’s growing jihadist problem were handled through regional and humanitarian channels. These crises were seen as regional failures rather than strategic contests involving outside powers. France, as the former colonial authority, was expected to carry the main burden. U.S. attention remained on the traditional Middle East.

Biden favored continuity and predictable channels of diplomacy. That approach kept the Gaza war from becoming a wider conflict and preserved stability inside a volatile region. The drawback is that it reinforced older boundaries at a time when other powers were ignoring them.

Trump’s Approach: Fewer Walls Between Regions

Trump views geopolitics as a landscape where formal boundaries matter less than practical opportunities. If a country has resources, markets, or the ability to limit Russian or Chinese influence, it becomes relevant. The result is a foreign policy that treats regions as overlapping spaces rather than fixed.

The Abraham Accords fit this approach. Under Trump, they were not Middle East agreements in a narrow sense. A state only needed a reason to integrate with the economic and security networks anchored in the Gulf and Israel. Geography was secondary. Practical benefits came first.

This approach produces a much larger strategic map incorporating a broad swath of Muslim-majority countries. Central Asia becomes linked to the Middle East through transit routes across the Caspian Sea. The Sahel becomes relevant because of mineral wealth and growing Chinese presence. Commercial ties give these relationships staying power even when political systems do not resemble each other. Trump’s style is often improvised, yet it opens doors that more cautious diplomacy leaves untouched.

Kazakhstan’s Move

Kazakhstan’s decision to join the Abraham Accords illustrates how far the boundaries have shifted. Under previous administrations, the country mattered for cooperation over Afghanistan and for balancing Russian and Chinese influence. It was rarely treated as part of a broader Middle Eastern system because its geography and political constraints seemed to place it firmly inside Moscow and Beijing’s shadow.

That context has changed. Russia’s war in Ukraine disrupted the export routes Kazakhstan relied on and exposed how vulnerable it is to Moscow’s control of pipelines. China stepped in with major infrastructure spending, but its growing presence created a different sort of dependency that Astana wants to hedge against. The country’s leaders now see value in new partners that offer an alternative to Russia and China.

Trump’s framework makes this shift possible. Kazakhstan has critical minerals, oil and refineries, and a position on emerging east–west corridors across the Caspian Sea that connect to Europe through Azerbaijan. As Russia’s regional position weakens, these routes become more important. Joining the Accords gives Kazakhstan a way to diversify its economy, build ties with the United States, and put space between itself and its larger neighbors.

The Sahel: Instability on the Margins

As new partnerships form across the Gulf and Central Asia, diplomatic attention is shifting. The Sahel, where over 50% of terror-related deaths occurred last year, is the clearest example. Mali’s capital Bamako is on the verge of being captured by a jidhaist group. Sudan’s civil war has shattered what remained of its governing institutions. Neighboring states are politically fragile.

The region has long been a geopolitical afterthought for Washington because France was expected to manage the problem as the former colonial power. Biden treated the Sahel within this older framework. The United States supported peacekeeping and humanitarian missions, but avoided deeper involvement.

Trump looks at the Sahel through a different lens. The region is still peripheral, yet its instability matters in ways that go beyond humanitarian concern. As France withdraws, Russia is filling the vacuum through Wagner and its successor groups, and China through economic and security partnerships. That is part of the logic of Trump’s recent call to intervene in Nigeria as Christians in the northern part of the country are targeted by the jihadists.

The Sahel is not part of the new commercial network forming between the Gulf and the Caspian. It is a peripheral zone where weak states, extremist groups, and outside powers converge. The difference is that Biden saw it as someone else’s problem, while Trump sees it as a security vacuum in a region with abudnant minerals to exploit.

This week’s headlines show how quickly the terrain is shifting. The Middle East is no longer a self-contained region. It is becoming the core of a larger system shaped by trade, minerals, transit routes, and power politics, and the United States finds itself defining that system through methods that break sharply with the old playbook.