The Next Front in the U.S.–China Trade War Isn’t Chips: It’s Rocks

Beijing is using its rare-earth dominance to pressure Washington

Rare earth elements, seventeen metals with names like neodymium, dysprosium, and terbium, are the hidden ingredients of modern life. They’re found in electric cars, wind turbines, fighter jets, and smartphones. They also make possible the chips, magnets, and sensors that power artificial intelligence. As AI spreads across industries, demand for these materials is exploding. The fight to control how they’re mined and refined is becoming one of the most important struggles in global politics.

AI might seem like something that lives in the cloud, but it depends on very real, physical stuff. Every large AI model is trained on massive computer servers that use energy-hungry chips and cooling systems. Each of those servers relies on copper wires, silicon wafers, and rare earth magnets.

A 2024 U.S. Department of Energy study predicted that electricity use from data centers could double or even triple by 2028 because of AI. Meeting that demand will require huge amounts of new materials, especially the metals needed for chips and advanced electronics.

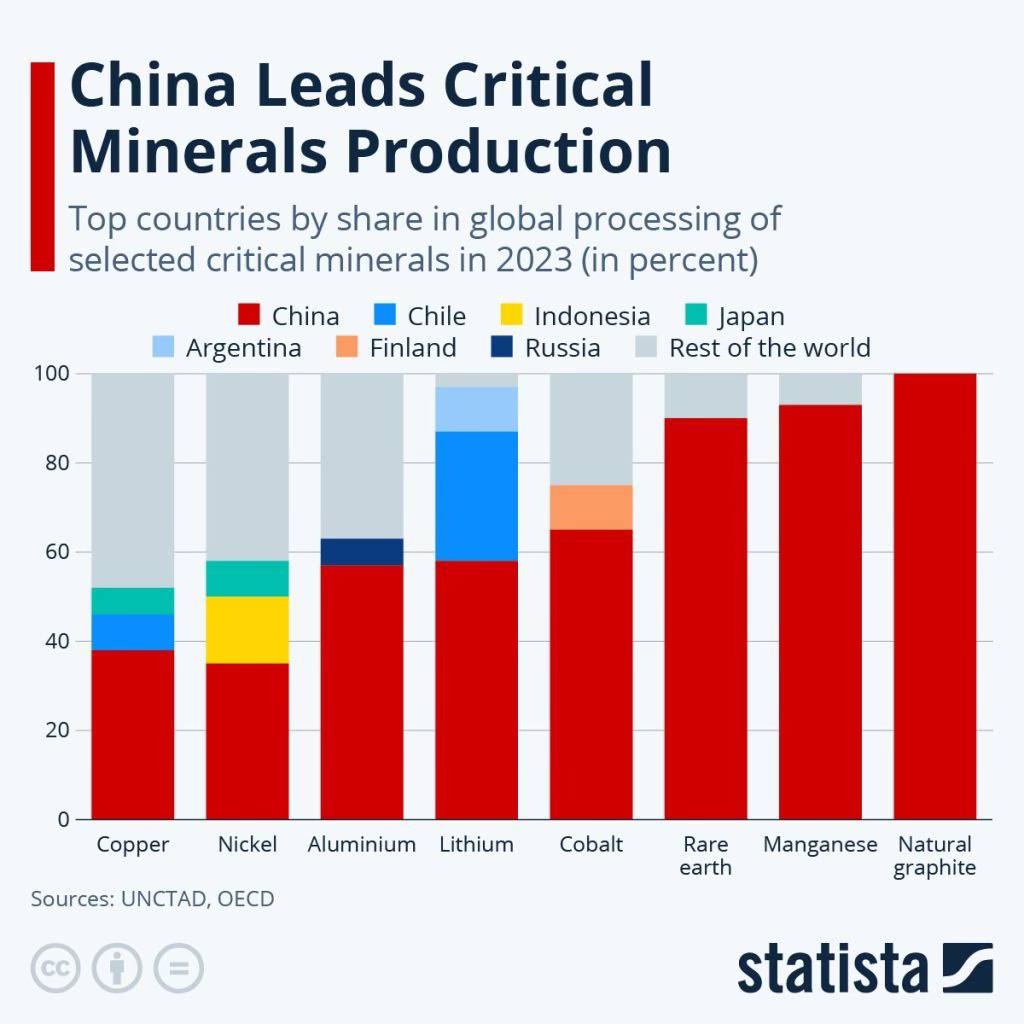

China saw this coming long before anyone else. Starting in the 1990s, it made a national effort to control the refining of rare earths and other critical minerals. Through state investment, export controls, and other policy tools, China built an industry that now dominates global supply.

It refines more than 80 percent of the world’s rare earths and over 90 percent of its polysilicon, which is used to make both semiconductors and solar panels. China doesn’t have most of the world’s raw materials, but it has the factories and processing plants that turn those materials into products. That’s where the real power lies.

Beijing is using its dominance in critical minerals as leverage in trade talks with Washington. Earlier this month, China tightened export controls on rare earths and related technologies, requiring government approval for any overseas sales or technology transfers.

The move came just weeks before planned U.S.–China negotiations and was widely read as an effort to remind Washington who holds the stronger position in the supply chain. The two powers are “playing supply-chain poker,” with China wagering that America’s need for refined minerals outweighs its leverage on high-end chips.

This latest round of curbs follows a familiar pattern. When the U.S. restricted China’s access to advanced semiconductors in 2023, Beijing hit back with limits on gallium and germanium exports, metals key to making chips.

Now, by adding rare earths and processing technologies to its control list, China has widened the contest from finished electronics to the raw materials beneath them. European manufacturers have already reported delays as Chinese export licenses slow approvals. What once seemed like a niche issue of resource management has become one of Beijing’s most effective pressure tools.

My own policy research on reshoring silicon refining shows how that leverage works. The United States has abundant raw materials, including quartz, lithium, and rare-earth deposits, but little ability to refine them.

Over decades, environmental costs, low prices, and competitor trade practices shifted the refining industry to China. Even minerals mined in allied countries are often sent there for processing before returning as finished components. Control of that step, not the mine itself, is what gives China lasting influence over global supply chains.

The U.S. and its allies are now trying to rebuild that missing industrial base. President Trump approved new Export-Import Bank financing for a heavy-mineral sands mining project in Australia, part of a wider push to counter Beijing’s grip on rare-earth refining.

The deal continues a Biden-era effort to back projects in Australia and Canada that can supply the same materials without Chinese involvement. Europe, meanwhile, opened its first rare-earth magnet plant this fall, and several U.S. start-ups are reopening domestic refineries that have been idle for decades.

This approach, often called nearshoring, means moving production closer to home by working with trusted partners instead of cutting ties completely. It’s a middle ground between depending too much on other countries and trying to do everything alone.

Both parties in Washington now see that having a steady supply of minerals is critical for U.S. defense, energy, and technology. Rebuilding the ability to process these materials will take time and money. Getting permits for new plants can take years, and environmental rules make projects more expensive, but without them, the U.S. will stay vulnerable to trade disruptions.

Whoever controls refining capacity controls the pace of the AI and clean-energy revolutions. China’s tightening of rare-earth exports is a warning that trade and foreign policy are now inseparable.

For the U.S. and its partners, the challenge is to “de-risk” without breaking the system entirely. This means building enough capacity to withstand pressure, while keeping trade open where it serves mutual interest. The outcome of that effort will shape not only the future of AI, but the balance of power in the twenty-first century.