The Resource Squeeze That Led to Pearl Harbor

The world is entering another age shaped by resource bottlenecks. Nations are scrambling for minerals for batteries, silicon for chips, and the electricity needed to run AI systems. When access to these inputs tightens, strategies shift. Supply chains harden into geopolitical boundaries. And rising powers face pressure from the limits of what their natural resources can support.

Explosion of ammunition magazines on the USS Shaw during the attack on Pearl Harbor. Colorized by ChatGPT 5.2

This is not a new pattern, and last Sunday’s 84th anniversary of the attack on Pearl Harbor is a reminder of this. Japan’s road to Pearl Harbor followed the same logic. It built a modern state without the resources to sustain one. When the United States cut off oil, the entire system snapped. The story is a reminder that great-power competition often turns violent only after the material foundations begin to fail.

Japan Industrializes

Japan encountered this reality early. When Commodore Matthew Perry of the US Navy sailed into Edo Bay in 1853, he forcibly began a process that opened a closed society to the modern world. The shock was not just military. Perry’s steamships demonstrated that Japan had no chance of surviving in an international system built around industrial capacity. The unequal treaties that followed made the point even clearer. Japan would modernize or it would be subordinated by imperial Western powers.

The Meiji Restoration in 1868 was the political expression of that conclusion. The new government centralized authority, dismantled old feudal privileges, and treated industrialization as vital for maintaining independence. Japanese officials learned from and copied Western industry. New shipyards, rail lines, and technical schools transformed the country within a generation. The speed was impressive, but the structural weakness was obvious. An island nation did not have the natural resources that made industrial power possible.

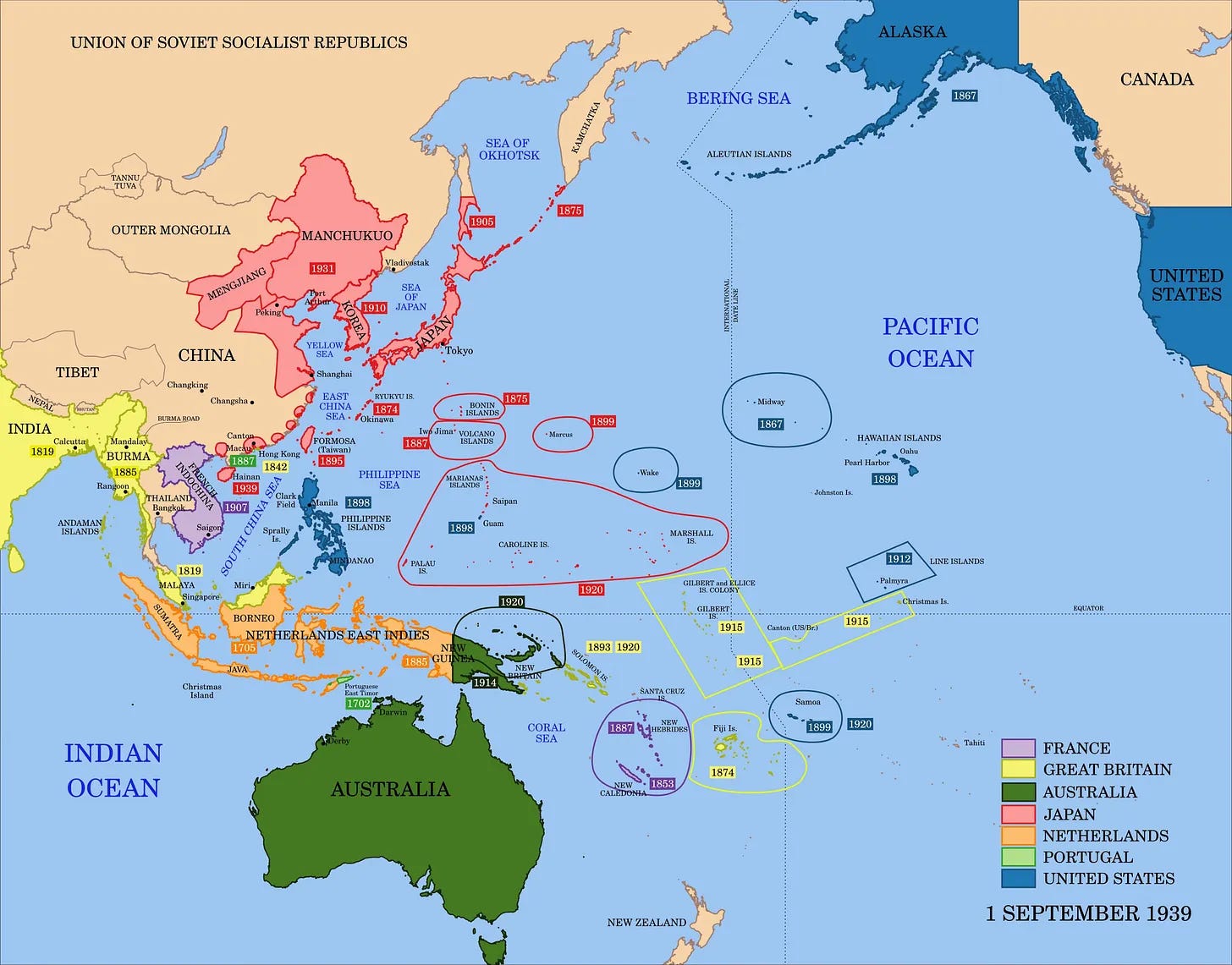

Japan’s early military victories masked this reality. In 1895, it defeated Qing China and brought Korea under its control. The victory signaled that modernization had produced real military capability. A decade later, Japan defeated Russia in the first modern war won by an Asian state against a major European empire. This elevated Japan into the ranks of great powers. It gained territory in Russia’s Far East and access to new coal and iron deposits.

By the 1920s, Japan had a modern fleet, an advanced aviation program, and industries capable of producing steel, chemicals, and machinery. Yet these capabilities rested on inputs imported over long distances. Japan had the ambitions of a continental power but the resource profile of a small island nation. This mismatch created chronic insecurity. In the 1930s, the pressure intensified. The Great Depression wrecked global trade, and protectionism spread. European empires still controlled the resources of Southeast Asia.

A Resource Curse

Japanese leaders concluded that the country’s survival required territorial control of key inputs. In 1931, Japan seized Manchuria, the northeastern region of China, and its coal, iron, and farmland. It expanded south along the coast. These campaigns secured markets and buffer zones, but they were driven by the deeper imperative to create self-sustaining industry. Even then, the most important input remained out of reach. Japan had no oil of its own.

By the late 1930s, Japan had become heavily dependent on the United States for petroleum, and Washington understood this leverage. As the war in China widened, the United States began to restrict key materials. Fuel and certain metals were placed under tighter export controls. These were signals that Japan’s expansion had limits and that the US felt its interests threatened. In 1940, President Roosevelt moved the Pacific Fleet from San Diego to Hawaii and ordered a military buildup in the Philippines, then a U.S. territory.

The turning point came in 1941. After Japan moved into southern Indochina (present-day Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia) to position itself closer to the oil fields of Southeast Asia, the United States imposed a full oil embargo. For Japan, this was an existential threat. Internal assessments estimated that Japan had eighteen months of fuel for military operations. Once the reserves ran out, Japan’s fleet would be immobilized, and its position in Asia would collapse.

Japan now faced a strategic dilemma. It could withdraw from China and accept American terms in exchange for restored access to oil. Or it could seize the Dutch East Indies (present-day Indonesia), whose reserves were the largest in the region. But that plan carried its own complications. Any move south risked a direct clash with U.S. forces in the Philippines, which sat across the sea lanes Japan needed to control. If Japan intended to take the oil fields, it would have to remove the U.S. Pacific Fleet as a threat.

War for Oil

Pearl Harbor was the product of this calculation. The decision for war was effectively made once the embargo began. The question became how to buy enough time to seize and secure the oil needed to sustain a long conflict. Japanese planners hoped a surprise strike would disable the Pacific Fleet for several months, long enough to take the Philippines and the Dutch East Indies. Pearl Harbor was meant to create the operational space required to rebuild Japan’s energy supply before the clock ran out.

The gamble was bold but doomed. Even after Japan seized the oil fields, its logistics were too fragile to support the war it had chosen. Tankers were vulnerable. Distances were long. U.S. submarines targeted shipping with growing effectiveness. The empire had acted out of necessity, but necessity did not erase the underlying imbalance. Japan had modernized into a great power without the resource foundations to remain one.

Japan’s path shows what happens when an industrial state depends on supply chains it does not control. Pressure builds gradually. Choices narrow. Strategic decisions become reactive. And when a rival cuts off access to a critical input, confrontation becomes more likely. Today’s world is not 1941, but the structure of competition is familiar. Nations are racing to secure minerals, energy, and industrial capacity, and this is already reshaping alliances. Control over these bottlenecks is drifting from the market into the realm of state power. That is when it becomes dangerous.