The Road to Damascus

The Scales Fall from War-torn Syria

In the fall of 2011, as a new college student, I distinctly remember the beginning of the Syrian Civil War. This period was a sort of awakening to the arena of global politics when a group of Islamist rebels threatened the overthrow of a brutal dictatorship. In the shadow of the Iraq War debacle and the announcement of the future end of hostilities in Afghanistan, it seemed like another potential quagmire for the United States.

Assad was a brutal dictator, but to my knowledge, had not committed war crimes up to that point. His regime had even assisted the United States in its War on Terror. And who were these rebels, after all? Would they simply replace an oppressive but non-threatening regime with a more oppressive one that could potentially support terrorist attacks? Neither side seemed great, and the Syrian people would suffer in any instance.

Fast forward to this week: Bashar al-Assad’s regime has fallen. The rapid advance of rebel groups, led by former Al-Qaeda affiliate Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), culminated in the capture of Damascus. Assad, along with his family, fled to Moscow, ending over 50 years of Assad family rule.

The collapse of the regime was shockingly swift, driven by weakened support from its foreign backers, Iran and Russia. According to Charles Lister of the Middle East Institute, the international community did not understand how weak the regime was. The dominoes fell quickly as HTS and a southern rebel coalition advanced, taking key cities like Aleppo, Hama, and Homs with little resistance. Damascus was surrendered without a fight.

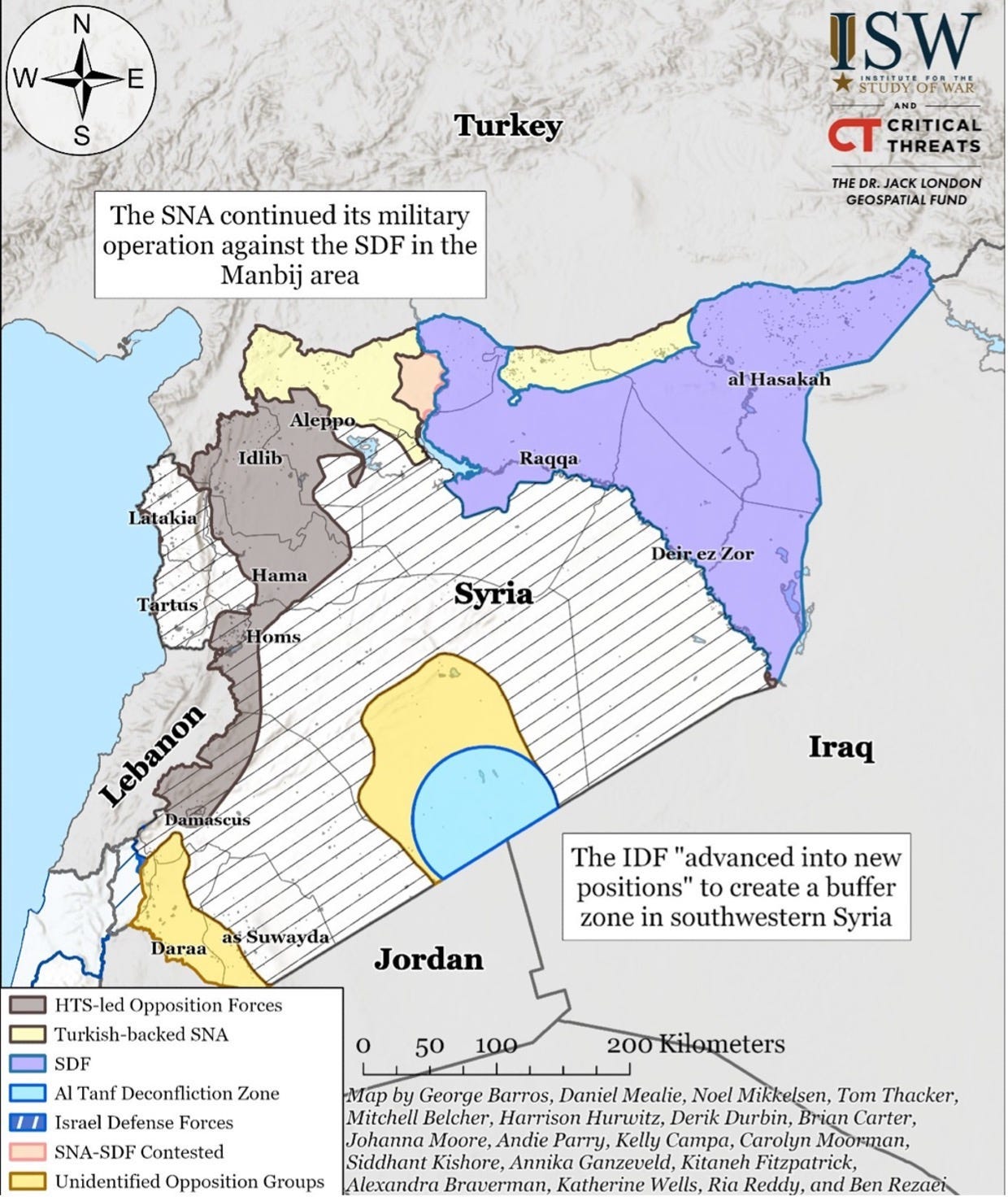

Understanding the fall of Assad’s regime requires an understanding of the Syrian Civil War. Syria was a patchwork of proxy groups, each backed by external powers. The Assad regime was propped up by Iran and Russia, who poured resources into keeping him afloat after the rise of ISIS in 2014. Meanwhile, the north of Syria became the stronghold of HTS, a rebel group supported by Turkey.

Turkey also occupied parts of northern Syria to create a buffer zone against the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), a Kurdish-led coalition that controls nearly a third of the country northeast of the Euphrates River. The Kurds, a stateless nation of 40 million, have long faced hostility from Turkey, particularly through Ankara’s fight against the PKK, a Kurdish separatist group.

The American-backed Free Syrian Army (FSA) controlled desert regions and operated out of Al-Tanf, a U.S. military base near the borders of Iraq, Jordan, and Syria. For much of the war, Assad held onto the population centers along a belt stretching from Aleppo to Damascus, as well as the Alawite-dominated coastal areas. However, two weeks ago, the balance shifted dramatically.

HTS launched a lightning campaign southward, sweeping through Aleppo and Hama before reaching Homs. Turkey had green-lit the operation months earlier, taking advantage of the inability of Russia and Iran to mount a serious defense. Sensing weakness, other factions made moves. The southern rebels captured the Jordanian border through negotiated surrenders. The FSA secured control over abandoned desert regions while the SDF solidified its hold on cities northeast of the Euphrates. The U.S., wary of a power vacuum, launched airstrikes to check ISIS.

Once HTS reached Damascus, Assad’s regime was finished. The surrender of Syrian forces in Homs had severed the capital from the Alawite heartland on the coast. Negotiations in Damascus led to the transfer of power to the HTS-led rebel coalition. Assad’s army was offered a general amnesty, and the coalition signaled an intent to respect minority rights. For now, Syria is divided into two main zones: Kurdish-controlled lands in the northeast and a rebel coalition governing the rest.

The geopolitical fallout from Assad’s collapse is significant. For Russia and Iran, Assad was a key ally and a crucial piece of their regional strategies. Russia’s naval base at Tartus, its only foothold on the Mediterranean, is now defenseless. This severely weakens Moscow’s ability to project power into the Middle East and Africa. Iran, meanwhile, has lost a vital part of its network of regional proxies.

It has lost Hezbollah, Hamas, and the Assad regime in the last year, and Iran’s air defense systems were destroyed by Israel. The ripple effects of Assad’s fall extend beyond Syria. In the Caucasus, Armenia and Azerbaijan are moving toward peace, and in Georgia, there is renewed energy to push back against Russian influence. These shifts reflect the diminished capacity of both Russia and Iran to assert themselves in their respective spheres of influence.

Domestically, Syria’s future remains uncertain. HTS portrays itself as a moderate, pragmatic force, eschewing its Islamist roots. They’ve emphasized diplomacy and inclusive governance to win over international observers. However, many question whether HTS can truly break from its roots and deliver on its promises to respect minority rights. The coalition’s ability to govern effectively in a war-torn, fractured country is an open question.

At the same time, the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) continue to control the northeast, creating a potential source of tension with HTS. The Kurds have long sought autonomy, and their presence in the new political landscape of Syria could complicate building a unified government.

The involvement of external powers like Turkey and the United States, adds another layer of complexity. Despite these uncertainties, there is a glimmer of hope. HTS’s willingness to grant amnesty to the Syrian Army and its presentation of a more inclusive vision for Syria suggest they will avoid the oppressive models of governance of other Islamist-led regimes. The group’s past role in fighting ISIS suggests it might prioritize stability over ideology.

For the first time in years, there is real potential for progress in Syria. Assad’s fall, rather than creating a power vacuum for terrorist groups, could mark the beginning of a new chapter for the country. A rebel-led Syria, guided by diplomacy and pragmatic governance, could pave the way for peace and stability, not just within its borders but across the Middle East.

With Iran’s regional ambitions unraveling and Russia’s influence waning, the power dynamics of the region are shifting in ways that could reduce conflict and open the door to lasting resolutions. The Syrian people have endured over a decade of unimaginable suffering. Now, with the Assad regime gone, there is a chance for something better. It’s a fragile hope, but after years of war and devastation, even a small step toward peace is worth supporting.

Sources

“Syria: Assad Regime Collapse Geneva Astana UN Wrong.” Foreign Policy. December 8, 2024. https://foreignpolicy.com/2024/12/08/syria-assad-regime-collapse-geneva-astana-un-wrong/.

“Assad Flees Syria: Damascus Fallen Rebels Capture Future.” Foreign Policy. December 8, 2024. https://foreignpolicy.com/2024/12/08/assad-flees-syria-damascus-fallen-rebels-capture-future/.

“Understanding the Syrian Civil War: A Guide from War on the Rocks.” War on the Rocks. Accessed December 8, 2024. https://warontherocks.com/understanding-the-syrian-civil-war-a-guide-from-war-on-the-rocks/.

“How Syria Rebels’ Stars Aligned for Assad’s Ouster.” Reuters. December 8, 2024. https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/how-syria-rebels-stars-aligned-assads-ouster-2024-12-08/.

“Syria: Assad Regime Collapsing Quickly.” Foreign Policy. December 5, 2024. https://foreignpolicy.com/2024/12/05/syria-assad-regime-collapsing-quickly/.