The War that Drew the Line

Immigration and the Mexican-American War

The Mexican-American War was a war that forged a generation of leaders. Most of the major military figures of the American Civil War, like Ulysses S. Grant, Robert E. Lee, William T. Sherman, first proved themselves on Mexican soil. Several became presidential candidates, too: General Zachary Taylor won the White House in 1848, Franklin Pierce in 1852, and Grant in 1868.

John C. Fremont, who helped seize California, became the first Republican presidential nominee in 1856, and the legendary general Winfield Scott lost to Pierce as the Whig Party nominee. But this war did more than elevate careers. It reshaped the continent and left behind a legacy that shapes how we think about borders, migration, and belonging.

Prelude to War

When Mexico gained independence from Spain in 1821, it inherited a vast territory stretching from Central America to the Pacific Northwest. Its leaders struggled to maintain control, especially of the thinly populated and governed northern reaches. Internal instability, regional uprisings, and power struggles undermined the young republic’s cohesion.

In 1836, General Santa Anna of Mexico led a rebellion that transformed the country into a unitary state, resulting in uprisings in several Mexican states. One of those uprisings, by American settlers in Texas, succeeded. Though Mexico never recognized independence, the United States annexed Texas in 1845.

That act triggered a crisis: Texas claimed the Rio Grande as its southern border, while Mexico insisted it was the Nueces River, far to the north. As an ardent believer in Manifest Destiny, the idea that the U.S. was destined to stretch from coast to coast, President James K. Polk saw opportunity. He ordered U.S. troops past the Nueces river into disputed territory to secure the Rio Grande. When fighting broke out, he asked Congress for a declaration of war.

A War for Conquest

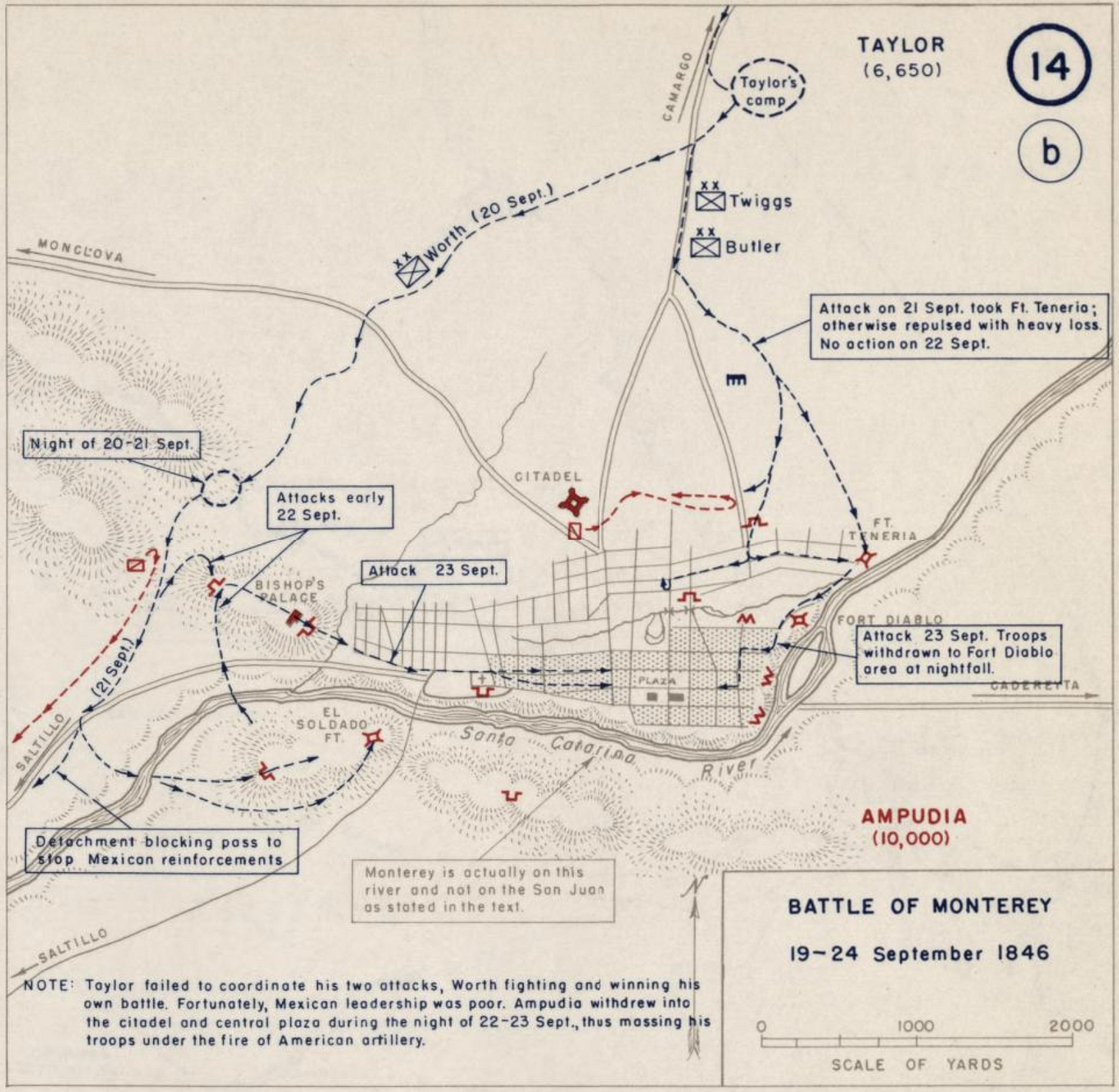

Polk’s vision for the conflict was expansive. He didn’t just want to defend Texas, he also wanted new territory. The war would be waged on multiple fronts. Zachary Taylor was tasked with pushing south from Texas into northern Mexico. He won key victories and captured the city of Monterrey after a grueling urban campaign.

General Winfield Scott was given command of an amphibious assault on Veracruz from the Gulf of Mexico followed by a march inland to Mexico City. His forces landed unopposed, laid siege to Veracruz, and then pushed through Mexico’s heartland, winning a series of battles and finally occupying the capital in September 1847. At the same time, General Stephen Kearny moved west from Kansas, capturing Santa Fe, establishing a military government, and aiding a rebellion by American settlers in California.

By early 1848, Mexico sued for peace. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo gave the United States more than 530,000 square miles of territory, land that would become California, Arizona, New Mexico, Utah, Nevada, and parts of Colorado and Texas. In exchange, the U.S. paid Mexico $15 million and assumed certain debts. The scale of the acquisition was staggering. With one treaty, the United States fulfilled its continental ambitions. For Mexico, it was a national humiliation that reshaped its politics.

But the treaty also created something more subtle and lasting: a new border that ran straight through the lives of tens of thousands of people. The line on the map moved. The people didn’t.

A Porous Border

Many Mexican citizens now found themselves in a new county. The treaty promised they would retain their property and be protected under American law. But those promises were unevenly kept. Many lost their land to legal maneuvering or outright seizure. Others were pushed to the margins in a society that treated them as second-class residents of a territory they had never agreed to join.

For decades, though, the border itself remained porous. Families crossed it to visit relatives or to find seasonal work. Trade flowed freely. Even conflict spilled across it. In 1916, Mexican revolutionary Pancho Villa led a raid into New Mexico, prompting a U.S. military expedition deep into northern Mexico, the last American invasion of its southern neighbor. Yet the idea of a fixed, militarized border hadn’t yet taken hold. That would come later.

In the early 20th century, immigration law began to harden. The 1917 Immigration Act imposed literacy tests and fees that disadvantaged Mexican migrants. In 1924, the U.S. created the Border Patrol to block Asian migrants who were entering through Mexico. Then came the Great Depression, and with it, mass deportations. Under pressure to reduce unemployment and deflect blame, U.S. officials deported over a million people of Mexican descent, many of them American citizens. It was a low point in the U.S.-Mexico relationship, but not the last.

Establishing Border Control

During World War II, the Bracero Program formalized cross-border labor and brought millions of temporary Mexican workers into the U.S. between 1942 and 1964. This ironically led to resentment as many American-born and settled Mexican laborers viewed the braceros as a source of wage suppression and lost jobs.

Even after the program officially ended, its legacy persisted in the form of employer resistance to unionization and continued reliance on vulnerable immigrant labor. In response to this and exploitative conditions in the agricultural sector In the labor activism surged among Mexican-American communities in the 1960s and 1970s. Figures like César Chávez and his United Farm Workers (UFW) mobilized tens of thousands of farmworkers in campaigns for higher wages, better working conditions, and union recognition.

In the 1990s, economic integration accelerated again. NAFTA opened markets and allowed goods to flow freely across the border. But people were another matter. Even as supply chains spanned the continent, immigration enforcement ramped up. Fences went up. Deportations increased. Public sentiment hardened. The U.S. now demanded that the southern border operate like a gate even though for most of its history, it had functioned more like a seam.

Changing Border Politics

This is reflected in the attitude of American politicians. In 1980, presidential candidate Ronald Reagan said of workers from Mexico: “Rather than talking about putting up a fence, why don’t we work out some recognition of our mutual problems, make it possible for them to come here legally.” Whereas today, Republican president Donald Trump bragged on the campaign trail about “the largest deportation operation in American history.”

The reality is more complicated. Many industries, especially in border states like Texas, would struggle with a sudden removal of immigrant labor from Mexico. Construction, agriculture, hospitality, and other low-wage, labor intensive industries would be impacted significantly. Trump himself has signaled less of a hard-line to spare these industries. It seems we want to deport the costs and keep the benefits of immigration from our southern neighbor.

That’s the legacy we’re living with today. The debate over immigration and border security with our southern neighbor didn’t begin in the 21st century. It began in 1848, when the United States drew a new line across the Southwest and absorbed a region, along with its people, culture, and tensions, that had never fully fit inside tidy national categories. For 300 years, it was under light administration by the Spanish Empire, then spent a short 25 years as part of Mexico, only to be absorbed into a growing, English-speaking United States.

Understanding that history doesn’t mean rejecting borders or abandoning enforcement. But it does mean recognizing that the current system is not necessarily natural, inevitable, or eternal. It’s the product of decisions made during and after a war that changed North America forever. And if we want to address immigration seriously, not just emotionally or politically, we have to start by understanding how the line got there in the first place.