Throwing Off the Soviet Yoke

Eastern Europe and Russia

I’ve covered the Ukraine War exhaustively, but never thoroughly discussed the recent historical backdrop. I’ve talked somewhat about the historical tensions in Europe, mainly between Russia and Eastern Europe. Why is Ukraine so resistant to Russian domination? Why are Poland and the Baltic states some of the most hawkish members of NATO, and most willing to boost military spending?

I’ve always believed that to understand the war in Ukraine, you have to dig deeper than battlefield reports. History lives in these countries’ bones. In revisiting old ideas and reading my old posts, the lines between then and now sharpen. The past is not gone. It is the soil from which today grows. There is a reason that the states that have suffered most at the hands of Russian imperialism are the most hawkish. They understand the stakes involved having personally experienced the consequences.

Ukraine

The historical relationship between Russia and Ukraine is complicated. The Black Sea has been a melting pot of cultures and empires, and Ukrainian identity is similarly complex. In fact, the first “Russian” state was the medieval Kyivan Rus’ with its capital in Kyiv, and predates the founding of Moscow.

But the recent history is one of subjugation. Ukrainian identity emerged in the early 19th century and Ukraine achieved independence as a strate briefly as the Ukrainian People’s Republic in 1917. It was founded in the chaos of the Russian Revolution, when the Bolsheviks under Vladimir Lenin overthrew the Russian monarchy to establish a communist state.

The Red Army reconquered most of the former Russian Empire and incorporated Ukraine into the newly-formed Soviet Union in 1922. In the 1930s, grain quotas imposed on Ukraine by the Soviet leadership led to a mass starvation event called the Holodomor that resulted in the death of 10% of Ukrainians. Another 6 million perished in World War II, including nearly one million Ukrainian Jews as part of the Holocaust.

Ukraine again achieved independence in 1991 when the Soviet Union fell, though its politics was regularly manipulated by Russia. Only 23 years later, Russia intervened militarily in 2014, seizing Crimea in response to the Maidan Revolution toppling a pro-Russian president. After subjecting Ukraine to 8 years of proxy war, it began its full-scale invasion in 2022, leading to an exodus of 8 million Ukrainians and 1 million Ukrainian military casualties.

Ukraine is protecting its sovereignty from an empire that has tried to destroy it at every turn and inflicted massive suffering now and in the past. It is not just self-defense, it is survival.

Baltic States

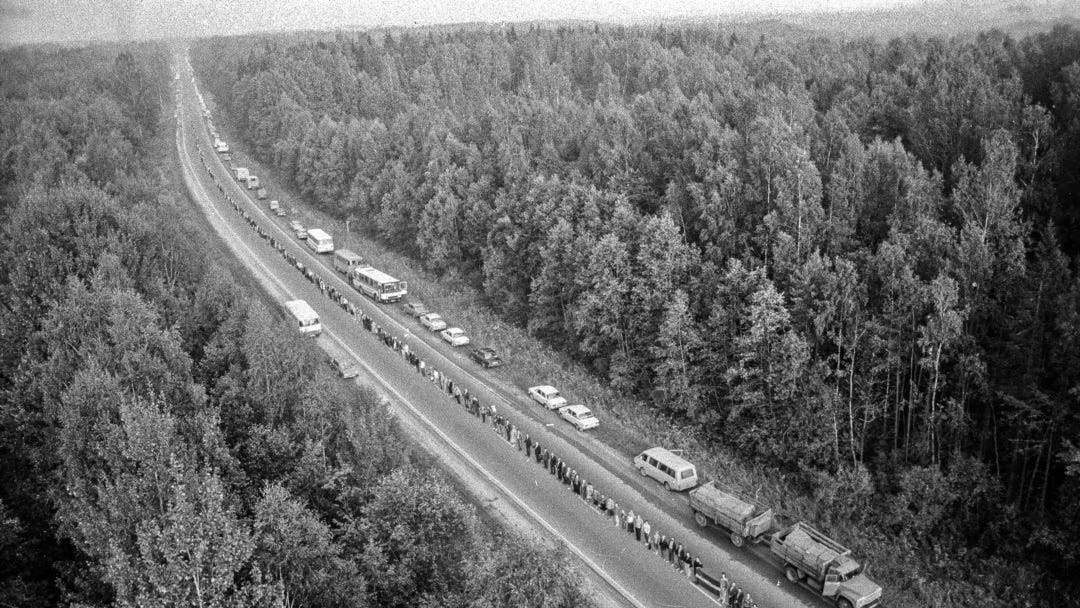

Similar to Ukraine, the Baltic states, as Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania are known, emerged as independent countries in the aftermath of the Russian Revolution. However, they survived independently until they were reconquered by the Soviet Union during its counteroffensive against the German invasion in WWII.

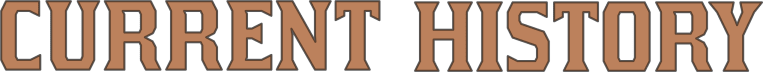

They were the first Soviet Republics to rise up and leave the Union. They engaged in a legendary non-violent protest of Soviet rule. In 1989, millions formed the “Baltic Way,” a human chain from Tallinn through Riga to Vilnius, demanding freedom. That protest was not only symbolic, it signaled that the memory of occupation was alive and organizing.

Today the Baltic states live under constant awareness of vulnerability. These states are small, and could be quickly overrun by Soviet ground forces. Estonia is only 200 miles across, and the three Baltic states are connected to their NATO allies only by a thin sliver of territory connecting Poland with Lithuania. Unlike Ukraine, they cannot absorb an invasion without serious risk. Thus, their political culture demands forward defense, robust alliances, and minimal tolerance for gray-zone coercion.

Decades of occupation brought deportation, cultural erasure, and Soviet control over every aspect of life. The Baltics and Ukraine share this memory: they know that Russian pressure seldom abates. Their identity and security are bound in resisting that pressure.

Poland

Poland has twice been dismembered by Russia. At one time, Poland-Lithuania was the second largest state in Europe. John Quincy Adams was the US ambassador at one point. But over a century it was split between three empires: Russia, Prussia (the predecessor to Germany), and Austria-Hungary. It regained independence after World War I, only to be split in two between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union in 1939, an invasion which precipitated WWII.

Similar to the rest of Eastern Europe, Poland suffered massively under both German occupation and Soviet reconquering. The Soviets mostly kept the Polish territories they had gained in their deal with the Nazis, while imposing totalitarian communist rule on a new Polish state that incorporated parts of Germany. Poland was the first Soviet satellite state to overthrow Communist rule in 1990.

Poland has a reputation of significant hostility against Russia. This is understandable. It knows the consequences from past history and now has the third largest standing army in NATO and spends 5% of GDP on its military.

The post-Communist era has not healed all memories. Poles recall decades of occupation, purges, and foreign domination. Their defensive posture today is born of those memories. Poland’s decision to invest massively in defense, to host NATO bases, and to refuse any complacency about its eastern flank is no accident — it is also about survival

Shifts in U.S. policy alarm Warsaw, which cannot afford to rely on others for security. For Poland, history teaches that when great powers vacillate, catastrophe may follow. Poland’s memory is not passive. It is active. It underpins policy, alliances, and refusal to be made vulnerable again.

Conclusion

For Ukraine, the Baltic States, and Poland, memory is not a nostalgic luxury, it is a foundation for survival. These nations did not wake up hawkish. They were made hawkish by centuries of being partitioned, occupied, and coerced. Their will to arm, to resist, to invest in alliances — it all flows from what was endured.

If we wish to understand Eastern Europe’s posture now, we cannot separate the present conflict from old injustices. The war in Ukraine is not a modern anomaly on a blank map. It is the current chapter of a long history of imperialism. These historical forces extend into tactics, strategy, and the human cost. But at the heart is this: the past does not sleep in Eastern Europe.

Further Reading

For anyone interested, a list of my Ukraine-related posts is below:

Ukraine Holds the Line, Barely

Considering Israel and Ukraine

The Fall of the Last European Empire

The Endgame of the Russia-Ukraine Conflict