Defense Stockpiling Is Back

The World War II Roots of America’s $12 Billion Critical Minerals Initiative

Last Monday, the Trumps administration announced a new effort to build a strategic reserve of critical minerals, dubbed “Project Vault.” The $12 billion initiative, built around a $10 billion credit line through the Export-Import Bank and $2 billion in private investment is meant purchase and stockpile essential minerals. At the same time, Congress introduced the SECURE Minerals Act of 2026, which would authorize approximately $2.5 billion to establish a Strategic Resilience Reserve.

The materials include a list of over fifty identified by the Interior Department as “critical”. This includes “rare-earths”, lithium, uranium, and copper, among others. These are the materials of modern technology. But the policy itself is not new.

The core problem is simple. Some supply chain inputs cannot be replaced quickly. Lithium does not move from a mine to battery-grade in weeks. Rare earths require complex refining processes found in only a few countries. When supply is disrupted, the constraint is not just money.

Strip away the language and the acronyms, and the idea is simple. The government wants to buy and store large quantities of certain industrial ingredients before a crisis forces it to. That realization is an old one.

During World War II, the United States discovered that economic dominance did not eliminate vulnerability. It exposed it.

Even before Pearl Harbor, American planners were studying supply risk. By 1939, officials inside the War Department were warning that the country depended heavily on imported manganese, chromium, tin, rubber, and other materials essential to steelmaking, engines, and munitions. These concerns led to the passage of the Strategic and Critical Materials Stock Piling Act in 1939, which allowed the government to acquire reserves in anticipation of emergency.

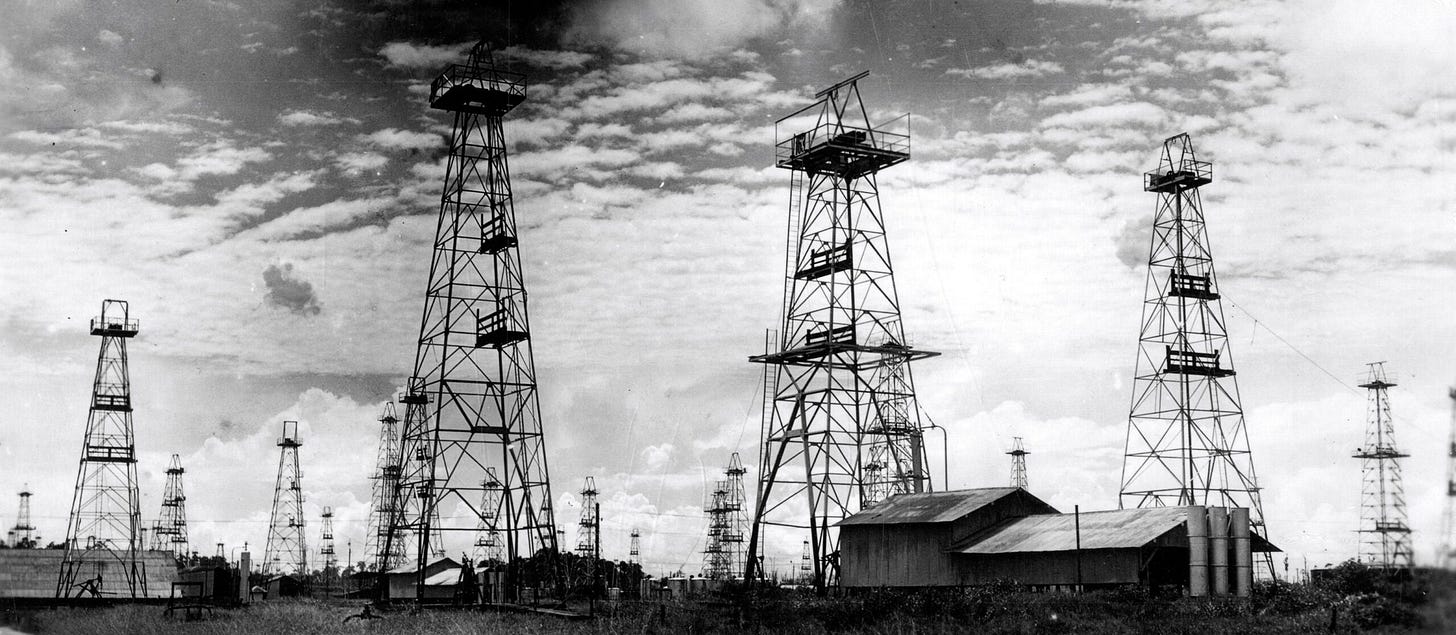

In 1941, the United States and its allies restricted oil exports to Japan in response to its expansion into Southeast Asia. Japan had limited domestic oil production and depended heavily on imported fuel. The embargo did not cripple Japan immediately. It started a clock. Japanese leaders understood that existing reserves would sustain operations for a limited period. After that, the military position would deteriorate sharply. Strategy became governed by depletion timelines.

The decision to attack Pearl Harbor was shaped in part by that timing problem. With reserves finite and access cut off, Japanese planners faced a narrowing window of 18 months before it ran out of oil. That led to a decisive attack to destroy the U.S. Pacific Fleet and seize the oil fields of modern-day Indonesia. The embargo did not simply apply pressure. It compressed time and forced a decision. That episode, explored in greater depth in a previous post, left a deep imprint on American strategic thinking.

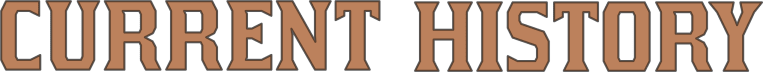

Once the United States entered the war, the problem intensified. When Japanese forces seized major rubber-producing regions in 1942, the United States suddenly lost access to 90 percent of its natural rubber supply.

Tires, truck mobility, aircraft components, and countless other systems depended on it. The federal government responded with an enormous synthetic rubber program, directing funding and coordinating private industry to build domestic production capacity from scratch. It worked, but it took time. In the interim, rationing was necessary to stretch existing supplies.

The lesson from this is not ideological, but practical. A modern industrial economy can be constrained by a handful of materials even if its factories remain intact. Money cannot immediately fix that constraint. Mines and refineries can’t be built overnight.

In 1946, Congress established the National Defense Stockpile. The law formalized wartime practice into standing policy. Its purpose was to maintain supplies of critical materials for emergencies. It was insurance against the bottlenecks experienced during the war.

Through the early Cold War, this logic remained intact. Many critical materials were sourced from politically unstable regions. Planners assumed that future conflicts or political upheaval could interrupt access. Over time, especially after the Cold War, confidence in global supply chains grew. “Just-in-time” logistics minimized inventory and stockpiles were drawn down.

Recent developments have reversed this trend.

Rare earth processing capacity is concentrated, monopolized by China. Opening new mines often requires a decade of permitting and construction. As in the 1940s, the constraint is not funding alone. It is the time required to build capacity.

Project Vault aims to secure and hold physical inventories of key minerals. Rather than rely exclusively on tariffs or export controls, which can trigger retaliation and accelerate escalation, policymakers are returning to an older instrument. Stockpiling does not eliminate dependence on international supply. It reduces the risk that sudden disruption will dictate policy.

World War II made clear that the economy is only as secure as its supply of critical materials. The embargo on Japan showed how quickly strategy contracts when reserves begin to run down. In the early Cold War, those lessons were built into permanent institutions. The revival of mineral reserves indicates that the structural risk never went away.

Different inputs, but the same problem: once supply chains tighten, choices narrow.